maharaja's of India BOWING IN FRONT OF BRITISH KING

Cavalry regiment at Coronation Durbar, 1903. An Indian cavalry regiment at the Coronation Durbar

GONE ARE THE DAYS OF POMP

NOW QUEEN ELIZABETH AT RAILWAY STATION DUE TO ECONOMIC DIFFICULTIES ,AFTER INDIA BECAME FREE

===============================================

THE 'DELHI DURBAR from Google Images

click on each image for details

In this article [hide]

- A British Durbar in Delhi

- The making of the Delhi Durbar 1911

- The official ceremonies of the Delhi Durbar spilled over a week-long spectacle of opulence from Dec 7-16, 1911.

- The Durbar on December 12, 1911 at Delhi

- The “Royal Boons” aka political policy announcements.

- The Delhi Durbar of 1911 was not without controversies

- A Garden Party, the revival of the mughal Jharokha-i-Darshan and a Museum

- The foundation for a “New Delhi” : an unexpected Ceremony!

- Was the Durbar of 1911 a successful event?

- The Delhi Durbar of 1911 proved to be a visual statement of Britain’s imperial might over India; as India’s nationalist movement gathered momentum, in the backdrop of global unrest, it cannot be denied that the Durbar also served the crucial purpose of gaining support from India’s people, especially its nobility.

- Delhi Durbar: a classroom discussion

The Delhi Durbar of 1911 represents a significant moment in Indian history. Hosted on December 12, 1911 it was the third (and last) of a series of formal coronation events held by the British Raj in India. The first was held in 1877 acknowledging Queen Victoria as the Empress of India and was followed by an event in honour of Edward VII in 1903. But it is only the 1911 event that the British monarchs attended in person.

Through paintings, photographs, a motion picture (in colour), postcards, memoirs, periodicals and several press-clippings, the Delhi Durbar may come across as a spectacular celebration – but dig deeper and you’d find it to be a crucial relationship building exercise that could offer many lessons for political image-building today.

In this story, we find out what went behind organizing an event of this scale, the people involved, the controversies and how the Delhi Durbar of 1911 fuelled the rise of a modern India.

A British Durbar in Delhi

Under the Persian King Darius’ rule, the celebration of Nowruz witnessed a gathering of kings and nobility from across the Empire. Gifts would be exchanged, followed by feasts and other rituals. The celebrations are well illustrated at Persepolis (Iran), the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire.

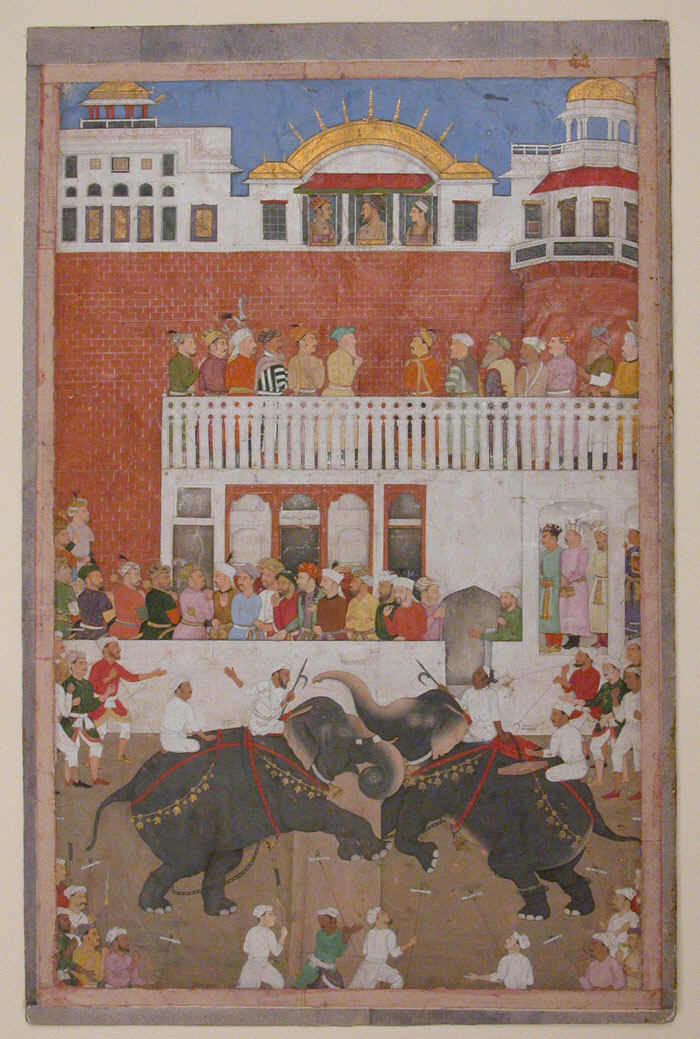

Centuries later, a similar practice was observed at the Mughal court, though the gatherings did not need were not restricted to a festive occasion such as Nowruz. The Mughal ‘Durbar’ referred to a formal court held by the Emperor to see and be seen by his subjects. The Emperor, in his finery, heard grievances and petitions; issued grants and engaged in an exchange of gifts (or nazar). Under the reign of Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire had reached its zenith; its wealth and opulence was inspiring to European monarchy as well. Take a look at this portrait of Akbar II in Durbar:

Paintings like this one commemorating state functions were produced in the court school of painters as souvenirs presented to high dignitaries and the emperor’s guests at the durbar.

While the Mughals had expanded their Empire through alliances and conquests, the British ambitions found a route through trade. As their influence in the Indian subcontinent increased, many of Mughal cultural practices were appropriated by the British – who believed themselves to be the ‘natural heirs’ to the Mughals in India.

Even though Calcutta had been the British hub of activity and power, each of the three Durbars were held in Delhi – the Mughal capital associated with prosperity. The British aspiration to replace Mughal glory is evident in this press-photo. Notice how the headline seems to stress on “City of the Moguls” ?

However, could there have been another motivation to choose Delhi as a location?

In his book, ‘An imperial vision: Indian architecture and Britain’s Raj’, historian Thomas R. Metcalf offers the view that this was “a move undertaken in large parts to enable the government to escape the uncomfortable political atmosphere of Calcutta, marked by continued and often violent demonstrations of nationalist sentiment since Lord Curzon’s 1905 partition of Bengal”

The making of the Delhi Durbar 1911

In the British Parliament in March 2011, King George V announced his desire to be coronated in Delhi. His announcement was not met with much enthusiasm – the costs of this trip, over £700,000 was to be borne by the Govt. of India and was surely a cause of great worry given the existing sentiments towards the Raj.

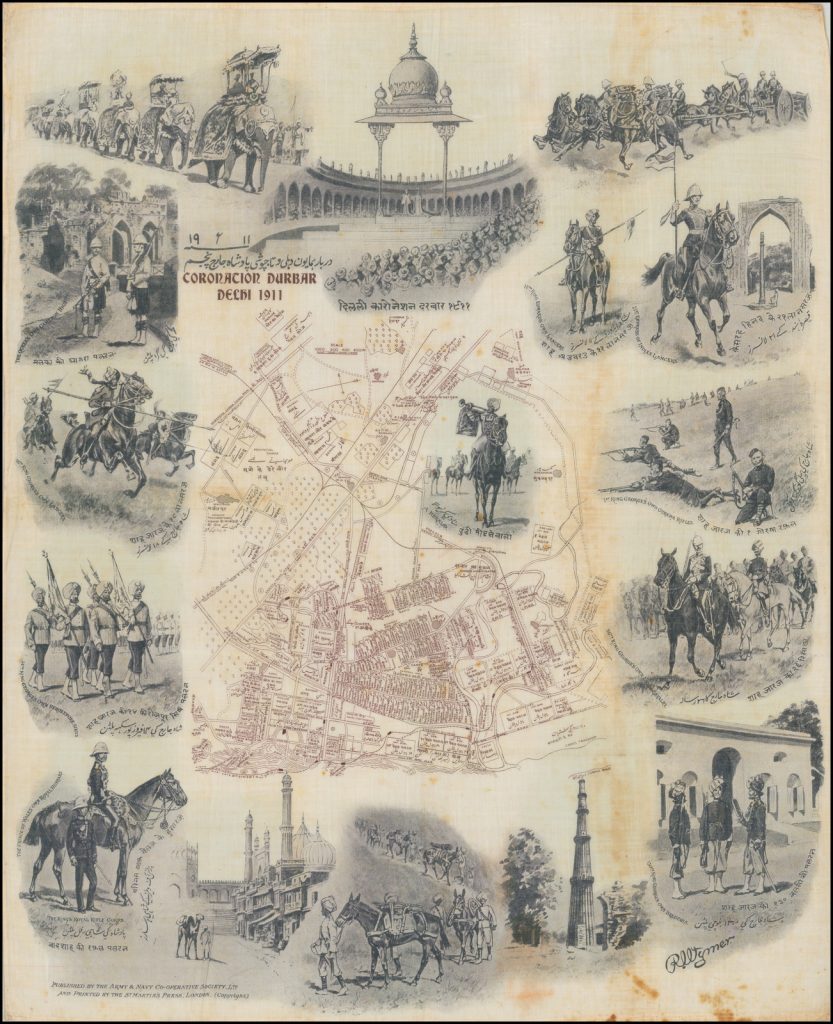

As preparations for this Coronation began, 30 villages of North Delhi gave way to a new “temporary city” built for thousands of guests and their entourage; replete with pathways, gardens and dining areas. There were reception tents, and separate areas for sporting events and military-troop reviews, communication centers for the press, and health facilities. The Nizam of Hyderabad went so far as to spend £100,000 for his own enclosure at a time when Hyderabad was grappling with a plague crisis.

40,000 tents spread across 25 sq miles made up this “Durbar City”, and were arranged hierarchically from the Viceroy’s tent. Notice how the King and Queen’s camp was safely tucked away, protected by a “sanitary zone”. Here’s a map from the National Army Museum, UK.

But who managed an event so impressive?

Rai Bahadur Narain Singh, who would go on to become one of the principal builders of Lutyen’s Delhi was the contractor responsible for the roads, camps and construction of the Durbar.

The Imperial Hotel in the city center (Janpath) traces its roots to him.

Two amphitheatres were to be constructed – a small one for special dignitaries, and a larger one for civilians and troops. At the center, there was to be a double-platform pavilion where the British royals would receive homages from Indian princes. The drawings detail the main structures and decorations used in the Delhi Durbar of 1911 and were created at the Mayo School of Arts under Bhai Ram Singh, who was Principal until 1913 and was responsible for the design of the Durbar.

Don’t miss the uncanny resemblance of the shamiana-dome to that of the Jama Masjid ! Take a look at this photograph of the 1911 Delhi Durbar and a painting by George Percy Jacomb.

Is it not reminiscent of the power and the resplendence of the Mughal court – with luxurious costumes and textiles, a bejewelled throne, inlayed and gilded architectural features – columns and arches? Perhaps that was the purpose – to gain the goodwill of the people as the Mughals had enjoyed. There’s another noticeable difference though – the earlier miniature painting featured a British dignitary, in a position subservient to the Emperor.

The event needed months of preparations that included preparing mandates for attendees, planning honouring-ceremonies, appropriate number of gun salutes, the procession of the Ruling Princes, inaugurations, garden tea parties – and managing all this was the then Viceroy Charles Hardinge. Credit where due, the British sure knew how to plan meticulously. In fact, India could have taken a leaf out of Hardinge’s book (literally!) while planning the Commonwealth Games in 2010.

The official ceremonies of the Delhi Durbar spilled over a week-long spectacle of opulence from Dec 7-16, 1911.

King George and Queen Mary entered India on December 2 via Bombay. The Gateway of India, which was meant to greet them could only make an appearance in a cardboard-miniature form.

The couple reached Delhi on December 7 and made their way through the Selimgarh Bastion of Delhi Fort towards the Ridge in a five-mile long procession amidst a series of gun-salutes. Over the next few days, they attended Polo, Hockey and Football matches, engaged in diplomatic ceremonies and unveiled a statue of King Edward VII (erected between the Fort and the Jama Masjid) – the cost (Rs. 5,00,000/- ) of which had been contributed by Indians. The statue, crafted by famous English sculptor Thomas Brock was said to be Delhi’s only equestrian one. If you’re wondering about its whereabouts – the statue was shifted to Coronation Park (the Delhi Durbar location) in the 1960s and eventually is believed to have made its way to Toronto.

A Coronation needs a Crown : ‘The Crown of India’

Because Britain’s Imperial Crown jewels are not allowed to be taken out of Great Britain, a new crown and tiara were commissioned for the traveling royals. The work was commissioned to the royal jewellers Garrard & Co. in London.

The resulting Delhi Durbar tiara for Queen Mary was “a complete circlet piece featuring 2,200 diamond scrolls and festoons set in platinum and gold with 10 emerald drops, which makes it particularly tall. In later years the 10 emeralds were removed, and Queen Mary continued to wear alterations of the tiara, each time commissioning Garrard to allow the tiara to have jewel swapping capabilities”.

King George V’s “Crown of India” incorporated 6,100 diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds, and weighed over a kilo. He is believed to have remarked that he felt :

“rather tired after bearing the new crown for 3.5 hours. It hurt my head and is pretty heavy.”

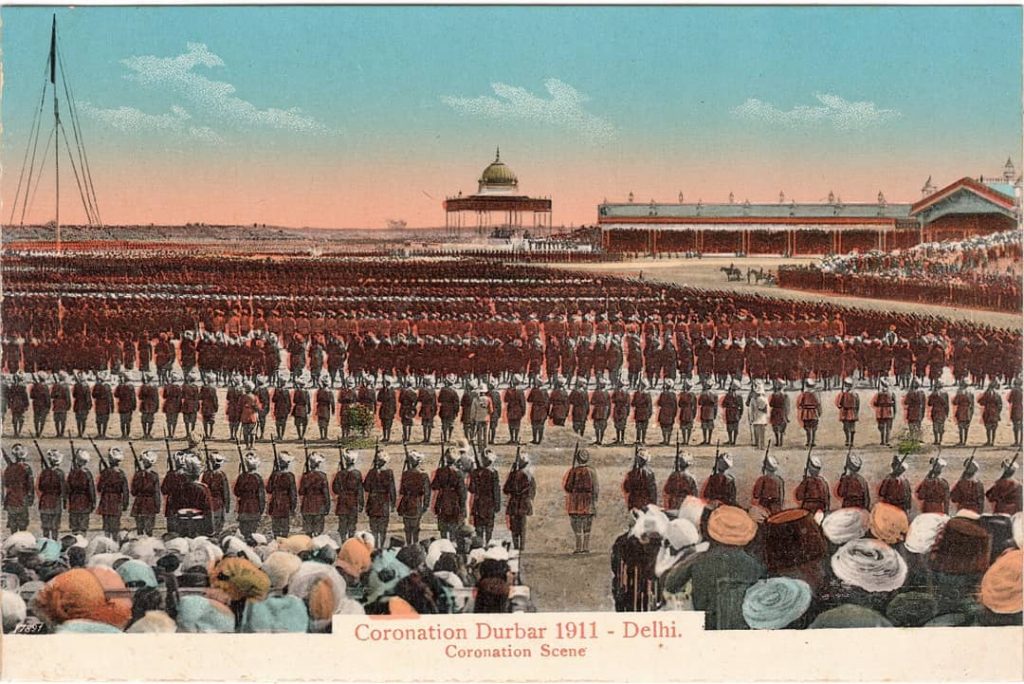

The Durbar on December 12, 1911 at Delhi

The Durbar , scheduled for the noon of December 12, was attended by 2,50,000 people. The amphitheatre had 12,000 seats reserved for Governors & other high ranking officials, and Indian royals. At the spectators mound, there were seats reserved for 50,000 people and 6000 school students. 20,000 troops representing all defence units were also present. The rest of the space was open to public. Here’s a toy-catalog by Beau-Geste that captures the regalia perfectly.

The British monarchs were seated on throne-chairs which had been cast by melting 96000 silver rupees; encrusted with gold plate and were exclusively crafted for the Coronation, at the Calcutta Royal Mint.

Sir Henry McMahon, the Emcee (Master of Ceremonies) opened the Durbar. The King’s welcome address was followed by a ‘homage’ by all attending dignitaries of who, the Nizam of Hyderabad ranked first. The Begum of Bhopal, also in attendance, was veiled head to toe in a cloth of gold and was only female-ruler paying homage.

Onlookers noticed the variety of salutations enough to make a mention in their diaries : while some simply bowed, many employed the gesture of throwing a bit of earth over the head; the Rajput Kings lay their swords at the feet of the Monarchs. Find the full list of Indian royals and attendees here. Can you tell who’s who?

The “Royal Boons” aka political policy announcements.

The proclamation was read in English as well as Urdu. The announcement included a reversal of the 1905 partition of Bengal (much to the relief of the crowd), assigning it the status of a Governor’s province. A new Lieutenant-Governorship in Council would administer the areas of Behar, Chota Nagpur and Orissa and there would be a redistribution of boundaries.

But it is another announcement left everyone stunned: the capital of the Empire was to shift to Delhi !

What did this mean for Calcutta? Europeans in Calcutta were shocked and rather disappointed. The Capital, the mouthpiece of Calcutta’s European business community termed it a ‘bolt from the blue’. The Englishman opined that it was a ‘thoughtless infliction of loss on a progressive community’. The Secretary of Bengal Chamber of commerce wrote to the Home Secretary hoping that the new capital would merely be a ceremonial one & that the city of Calcutta will continue being the commercial center. The Bengalee (representing some of Bengal’s most influential names) however felt the decision might be in the interest of Calcutta by leading to provincial autonomy.

The Mercury reported that the cost of shifting the capital would be £4,000,0000

There were welfare announcements as well (grants for the promotion of education, increased salaries for Civil Service officers and military personnel) as relief for certain prisoners.

The Durbar closed with the Royals moving from the ‘Shamiana’ towards the Royal Pavilion, their robes carried by Page-Boys. Ten young princes, sons of maharajas, were chosen as the king’s and queen’s “pages”. They were drilled and rehearsed for days, how to hold the train of the royal robes up at their shoulder height, as their majesties walked to their thrones / seats.

The Delhi Durbar of 1911 was not without controversies

A day after the durbar, the New York Times reported:

With splendid Oriental pageantry George V, King of Great Britain and Ireland, and his consort, standing on a marble dais under a golden dome, were yesterday proclaimed Emperor and Empress of a nation with 293,000,000 inhabitants. …Americans must inevitably be struck by the strange anachronism of this ceremony in a democratic age.

It is no secret that India is full of discontent, as it has been since the day of John Company. … Much of recent Indian legislation has increased discontent. Taxation is too heavy. Many minor reforms are looked for. The Emperor’s long journey and personal participation in the Durbar will fail in its effect if it does not result in at least some temporary allaying of the vast empire’s chronic unrest.

Read: The Times of India report

Political Resistance:

In the early 1900s, the public sentiment towards the Raj was not very positive. Fuelled by Lord Curzon, the Partition of Bengal in 1905 had caused massive unrest. Indians were already rallying for ‘Swaraj’ (self-government) and Lokmanya Tilak had launched the Swadeshi movement for which he was jailed in 1908 on charges of sedition. Let’s also not forget the elective policy of Divide & Rule propagated by the Morley-Minto “reforms” of 1909. The 1910 Press Act sought to curtail the rising influence of India’s vernacular media. In the backdrop of these events, it is safe to say that the Durbar was designed to win public favour. But would that be possible?

At the Durbar, where everyone was dressed in their finest – the Maharaja of Patiala alone wore jewels worth half a crore – Maharaja Sayajirao, Gaekwad of Baroda, chose a plain cotton white robe. As per protocol, the Indian royals were to bow three times before the Monarchs, retreating face-forward. Sayajirao refused to submitting “to perform like some circus animal”; he merely nodded his head at the King once, and turning his back (considered disrespectful), one hand in trouser pocket, twirling a swagger stick with the other, sauntered away. His actions were understood as “seditious” by Hardinge and other British officials.

Moti Lal Nehru (dressed for the occasion, tailored from London) too, berated Gaikwad’s conduct in a letter to his son, terming it a setback for the “Swaragists”. Sayajirao, however, in a letter to Jawaharlal Nehru firmly stated that he wished he didn’t have to “see this day”.

The Maharao of Mewar, did arrive at the Delhi Railway Station but then “his conscience revolted, and ordered his special train to turnabout and take him home” ! If you ever find yourself in Udaipur, head to the City Palace museum where you will find a chair that had been stationed for him at the Delhi Durbar of 1911.

Pig – Currency

Every coronation was followed by a new issue of coins bearing the sovereign’s face. Colonial currency policies adversely impacted India (a story for another time)- but King George V’s rule witnessed a controversial episode over new coinage. One side of the new coins featured three emblems of Britain : the Rose of England, the Thistle of Scotland, and the Shamrock of Ireland; with the Indian lotus appearing on top.

The problem was with the side featuring the King’s face. In the design, he wears the “Order of the Indian Empire”, decorated with roses, peacocks and elephants. However, a poor quality of engraving resulted in the elephant resembling a pig – this caused outrage amidst the Muslim community who felt quite insulted.

A Garden Party, the revival of the mughal Jharokha-i-Darshan and a Museum

The Hayat Baksh, ‘jewel of Shah Jahan’s palace gardens’ in the Red Fort complex had been in shambles when Hardinge first inspected it. By December 13, it had been restored to it’s original glory by the ASI – suitable to host a Garden Party (one of the last functions of the Durbar).

At this party, special arrangements were made for the “Purdah Ladies ” – over one hundred of the leading Maharanis, Ranis and other ladies of India were present to meet the Queen. A token of their first meeting – an emerald brooch gifted by the Indian Queens has since then been a family heirloom for the British!

A fascinating occurrence in this royal-tour was the revival of the Mughal Jharokha-i-Darshan & the narratives surrounding it.

It was the Mughal emperor Akbar who first initiated the Jharokha-e-Darshan – he would appear on an east-facing balconied and canopied window of his fort to offer darshan to his followers. One cannot know where he got the idea from, but historians have assessed this as ‘an altered form of idol worship where the king himself appeared in person, framed by the window and the canopy’.

[Move the image slider to see the darshan-window at different times.]

Generations later, Indians continue to find themselves hero-worshipping a poster of movie-stars – who by the way, also appear on their balconies waving to crowds early in the morning till this day! More than the Mughals, the credit for this belongs to colonial rule.

The jharokha-event was painted, and written about extensively.

It was perhaps a significant moment in the reign of George V as illustrated in this series of cigarette cards issued by Wills.

One of the narratives goes as far as projecting George V as the messiah for Sikhs, Hindus, Jains, Mohammedans alike and as a unifying force who had crossed oceans to come and give them the salvation they had been waiting for! Such writing can only be interpreted today as propaganda – and reflects a constructed narrative that the British were so keen to promote.

Another book even visualises King George V as a reincarnation of Shah Jahan, seated at the Jharokha.

The Who’s Who in India describes the Jharokha thus:

“That as many as possible of his Indian subjects should be gratified with a sight of their Sovereign, His Majesty, with his Royal Consort, graciously made their appearance during the afternoon at the historic Jarokha in the Masumum Burj, where immense crowds who had come to visit the Badshahi Mela passed before the Royal presence …processions representing the various religions, Hindu, Sikh, Musalman, Jain, and the Arya Samaj were to march on to the Mela area. A military tattoo was given at the Mela at sunset by the massed bands, and a display of fireworks took place…Hundreds of thousands of Their Majesties’ humbler subjects thus had the supreme pleasure of participating in the universal rejoicings and returned to their homes in all parts of the country satisfied that they had indeed seen their Emperor and Empress.

The Dewan-i-Khas was reserved for the use of the Royals, but the other historic buildings of the Red Fort were open to guests ; the Museum of Delhi antiquities specially formed by the Punjab Government for this occasion, and located in the Mumtaz Mahal, was also open to everyone.

On display were arms and armoury, “mutiny relics”, fine examples of the arts of seal-engraving and calligraphy, portraits of famous people in the history of the Mughal Empire, as well as a large number of pictures of archaeological interest. Much of this was loaned by Indian royals including Udaipur, Gwalior, Jodhpur, Bhopal, Bikaner and Alwar.

On 14 December the King-Emperor presided over an Investiture ceremony, inspecting a military parade of 50,000 troops, and the Police force. Twenty-six thousand eight hundred (26,800) Delhi Durbar Medals in silver were awarded to the men and officers of the British and Indian Armies who participated in the 1911 event. A further two hundred were struck in gold, a hundred of which were awarded to Indian princely rulers and the highest ranking government officers.

The foundation for a “New Delhi” : an unexpected Ceremony!

December 15 witnessed an unexpected ceremony at the Government of India Camp, when the King and Queen laid the foundation stones for a new Imperial Capital. They additionally served as visible memorials of the Royal visit. The King is believed to have reportedly said :

“It is my desire that the planning and designing of the public buildings to be erected will be considered with the greatest deliberation and care, so that the new creation maybe in every way be worthy of this ancient and worthy city.”

The departure of the Royals on 16th was marked by a 101 gun salute and yet another procession.

Was the Durbar of 1911 a successful event?

Even though there had been 2 earlier Durbars, no ruling monarchs had ever visited the subcontinent. In the absence of any precedent, the stakes were quite high and the purpose clear – the event was meant to herald a new phase of the Raj, and signal a new political direction. The Durbar generated extensive media coverage and scholarly attention long after it had concluded. Upon his return, George V is said to have reflected positively on the outcome of the Durbar. As per him, he had felt genuinely welcome by the aristocracy and masses alike. Interestingly, Indian media did not think so. An assassination attempt on Hardinge in 1912 also tells another story.

The British used the power of media effectively to reinforce the subjugation of India and it’s aristocracy. A simple Google search will reveal the multiple postcards, videos that were circulated globally and bear testimony to the public display of hierarchy.

The Delhi Durbar of 1911 proved to be a visual statement of Britain’s imperial might over India; as India’s nationalist movement gathered momentum, in the backdrop of global unrest, it cannot be denied that the Durbar also served the crucial purpose of gaining support from India’s people, especially its nobility.

................................................................................................................ m

Bydlení je rubrika webu Zprávy Novinky Na Zprávy Novinky se dočtete jak moderně bydlet Co s nájemním bydlením Vám poradí redakce Zprávy Novinky Rubriku Bydlení pro Vás připravuje Bydlení cz Jak se žije na Moravě Posílejte nám články a fotografie vašeho Bydlení Moderní Bydlení

ReplyDeletebydlení