Europeans being entertained by dancers and musicians in a splendid Indian house in Calcutta during Durga puja’ by William Princep.

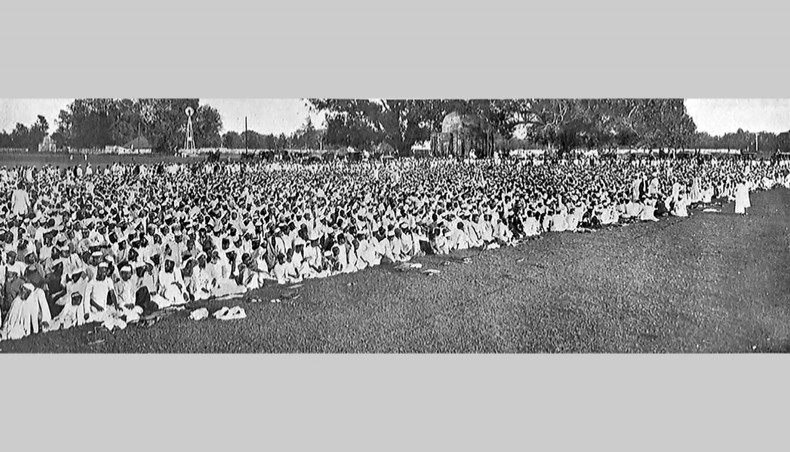

Europeans being entertained by dancers and musicians in a splendid Indian house in Calcutta during Durga puja’ by William Princep. bottom photo shows "thanksgiving gathering" in Dacca for partition of Bengal!

Britain's divide and rule politics started in 1905 in India!

culminated when Britain colluded with Jinnah for pakistan

World War I and after

During World War I the great powers made a number of decisions concerning the future of Palestine without much regard to the wishes of the indigenous inhabitants. Palestinian Arabs, however, believed that Great Britain had promised them independence in the Ḥusayn-McMahon correspondence, an exchange of letters from July 1915 to March 1916 between Sir Henry McMahon, British high commissioner in Egypt, and Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, then emir of Mecca, in which the British made certain commitments to the Arabs in return for their support against the Ottomans during the war. Yet by May 1916 Great Britain, France, and Russia had reached an agreement (the Sykes-Picot Agreement) according to which, inter alia, the bulk of Palestine was to be internationalized. Further complicating the situation, in November 1917 Arthur Balfour, the British secretary of state for foreign affairs, addressed a letter to Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild (the Balfour Declaration) expressing sympathy for the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people on the understanding that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” This declaration did not come about through an act of generosity or stirrings of conscience over the bitter fate of the Jewish people. It was meant, in part, to prompt American Jews to exercise their influence in moving the United States to support British postwar policies as well as to encourage Russian Jews to keep their nation fighting.

Palestine was hard-hit by the war. In addition to the destruction caused by the fighting, the population was devastated by famine, epidemics, and Ottoman punitive measures against Arab nationalists. Major battles took place at Gaza before Jerusalem was captured by British and Allied forces under the command of General Sir Edmund (later 1st Viscount) Allenby in December 1917. The remaining area was occupied by the British by October 1918.

At the war’s end, the future of Palestine was problematic. Great Britain, which had set up a military administration in Palestine after capturing Jerusalem, was faced with the problem of having to secure international sanction for the continued occupation of the country in a manner consistent with its ambiguous, seemingly conflicting wartime commitments. On March 20, 1920, delegates from Palestine attended a general Syrian congress at Damascus, which passed a resolution rejecting the Balfour Declaration and elected Fayṣal I—son of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, who ruled the Hejaz—king of a united Syria (including Palestine). This resolution echoed one passed earlier in Jerusalem, in February 1919, by the first Palestinian Arab conference of Muslim-Christian associations, which had been founded by leading Palestinian Arab notables to oppose Zionist activities. In April 1920, however, at a peace conference held in San Remo, Italy, the Allies divided the former territories of the defeated Ottoman Empire. Of the Ottoman provinces in the Syrian region, the northern portion (Syria and Lebanon) was mandated to France, and the southern portion (Palestine) was mandated to Great Britain. By July 1920 the French had forced Fayṣal to give up his newly founded kingdom of Syria. The hope of founding an Arab Palestine within a federated Syrian state collapsed and with it any prospect of independence. Palestinian Arabs spoke of 1920 as ʿām al-nakbah, the “year of catastrophe.”

Uncertainty over the disposition of Palestine affected all its inhabitants and increased political tensions. In April 1920 anti-Zionist riots broke out in the Jewish quarter of Old Jerusalem, killing several and injuring scores. British authorities attributed the riots to Arab disappointment at not having the promises of independence fulfilled and to fears, played on by some Muslim and Christian leaders, of a massive influx of Jews. Following the confirmation of the mandate at San Remo, the British replaced the military administration with a civilian administration in July 1920, and Sir Herbert (later Viscount) Samuel, a Zionist, was appointed the first high commissioner. The new administration proceeded to implement the Balfour Declaration, announcing in August a quota of 16,500 Jewish immigrants for the first year.

In December 1920, Palestinian Arabs at a congress in Haifa established an executive committee (known as the Arab Executive) to act as the representative of the Arabs. It was never formally recognized by the British and was dissolved in 1934. However, the platform of the Haifa congress, which set out the position that Palestine was an autonomous Arab entity and totally rejected any rights of the Jews to Palestine, remained the basic policy of the Palestinian Arabs until 1948. The arrival of more than 18,000 Jewish immigrants between 1919 and 1921 and land purchases in 1921 by the Jewish National Fund (established in 1901), which led to the eviction of Arab peasants (fellahin), further aroused Arab opposition that was expressed throughout the region through the Christian-Muslim associations. On May 1, 1921, more serious anti-Zionist riots broke out in Jaffa, spreading to Petaḥ Tiqwa and other Jewish communities, in which nearly 100 were killed. An Arab delegation of notables visited London in August–November 1921, demanding that the Balfour Declaration be repudiated and proposing the creation of a national government with a parliament democratically elected by the country’s Muslims, Christians, and Jews. Alarmed by the extent of Arab opposition, the British government issued a White Paper in June 1922 declaring that Great Britain did “not contemplate that Palestine as a whole should be converted into a Jewish National Home, but that such a Home should be founded in Palestine.” Immigration would not exceed the economic absorptive capacity of the country, and steps would be taken to set up a legislative council. These proposals were rejected by the Arabs, both because they constituted a large majority of the total mandate population and therefore wished to dominate the instruments of government and rapidly gain independence and because, they argued, the proposals allowed Jewish immigration, which had a political objective, to be regulated by an economic criterion.

The British mandate

In July 1922 the Council of the League of Nations approved the mandate instrument for Palestine, including its preamble incorporating the Balfour Declaration and stressing the Jewish historical connection with Palestine. Article 2 made the mandatory power responsible for placing the country under such “political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish National Home…and the development of self-governing institutions.” Article 4 allowed for the establishment of a Jewish Agency to advise and cooperate with the Palestine administration in matters affecting the Jewish national home. Article 6 required that the Palestine administration, “while ensuring that the rights and position of other sections of the population are not prejudiced,” under suitable conditions should facilitate Jewish immigration and close settlement of Jews on the land. Although Transjordan—i.e., the lands east of the Jordan River—constituted three-fourths of the British mandate of Palestine, it was, despite protests from the Zionists, excluded from the clauses covering the establishment of a Jewish national home. On September 29, 1923, the mandate officially came into force.

Palestine was a distinct political entity for the first time in centuries. This created problems and challenges for Palestinian Arabs and Zionists alike. Both communities realized that by the end of the mandate period the region’s future would be determined by size of population and ownership of land. Thus the central issues throughout the mandate period were Jewish immigration and land purchases, with the Jews attempting to increase both and the Arabs seeking to slow down or halt both. Conflict over these issues often escalated into violence, and the British were forced to take action—a lesson not lost on either side.

Arab nationalist activities became fragmented as tensions arose between clans, religious groups, and city dwellers and fellahin over the issue of how to respond to British rule and the increasing number of Zionists. Moreover, traditional rivalry between the two old preeminent and ambitious Jerusalem families, the Ḥusaynīs and the Nashāshībīs, whose members had held numerous government posts in the late Ottoman period, inhibited the development of effective Arab leadership. Several Arab organizations in the 1920s opposed Jewish immigration, including the Palestine Arab Congress, Muslim-Christian associations, and the Arab Executive. Most Arab groups were led by the strongly anti-British Ḥusaynī family, while the National Defense Party (founded 1934) was under the control of the more accommodating Nashāshībī family. In 1921 the British high commissioner appointed Amīn al-Ḥusaynī to be the (grand) mufti of Jerusalem and made him president of the newly formed Supreme Muslim Council, which controlled the Muslim courts and schools and a considerable portion of the funds raised by religious charitable endowments. Amīn al-Ḥusaynī used this religious position to transform himself into the most powerful political figure among the Arabs.

Initially, the Jews of Palestine thought it best served their interests to cooperate with the British administration. The World Zionist Organization (founded 1897) was regarded as the de facto Jewish Agency stipulated in the mandate, although its president, Chaim Weizmann, remained in London, close to the British government; the Polish-born emigré David Ben-Gurion became the leader of a standing executive in Palestine. Throughout the 1920s most British local authorities in Palestine, especially the military, sympathized with the Palestinian Arabs, whereas the British government in London tended to side with the Zionists. The Jewish community in Palestine, the Yishuv, established its own assembly (Vaʿad Leumi), trade union and labour movement (Histadrut), schools, courts, taxation system, medical services, and a number of industrial enterprises. It also formed a military organization called the Haganah. The Jewish Agency came to be controlled by a group called the Labour Zionists, who, for the most part, believed in cooperation with the British and Arabs, but another group, the Revisionist Zionists, founded in 1925 and led by Vladimir Jabotinsky, fully realized that their goal of a Jewish state in all of Palestine (i.e., both sides of the Jordan River) was inconsistent with that of Palestinian Arabs. The Revisionists formed their own military arm, Irgun Zvai Leumi, which did not hesitate to use force against the Arabs.

British rule in Palestine during the mandate was, in general, conscientious, efficient, and responsible. The mandate government developed administrative institutions, municipal services, public works, and transport. It laid water pipelines, expanded ports, extended railway lines, and supplied electricity. It was less assiduous in promoting education, however, particularly in the Arab sector, and it was hampered because it had to respond to outbreaks of violence both between the Arab and Jewish communities and against itself. The aims and aspirations of the three parties in Palestine appeared incompatible, which, as events proved, was indeed the case.

There was little political cooperation between Arabs and Jews in Palestine. In 1923 the British high commissioner tried to win Arab cooperation by offers first of a legislative council that would reflect the Arab majority and then of an Arab agency. Both offers were rejected by the Arabs as falling far short of their national demands. Nor did the Arabs wish to legitimize a situation they rejected in principle. The years 1923–29 were relatively quiet; Arab passivity was partly due to the drop in Jewish immigration in 1926–28. In 1927 the number of Jewish emigrants exceeded that of immigrants, and in 1928 there was a net Jewish immigration of only 10 persons.

Nevertheless, the Jewish national home continued to consolidate itself in terms of urban, agricultural, social, cultural, and industrial development. Large amounts of land were purchased from Arab owners, who often were absentee landlords. In August 1929 negotiations were concluded for the formation of an enlarged Jewish Agency to include non-Zionist Jewish sympathizers throughout the world.

This last development, while accentuating Arab fears, gave the Zionists a new sense of confidence. In the same month, a dispute in Jerusalem concerning religious practices at the Western Wall—sacred to Jews as the only remnant of the Second Temple of Jerusalem and to Muslims as the site of the Dome of the Rock—flared up into serious communal clashes in Jerusalem, Ẓefat, and Hebron. Some 250 were killed and 570 wounded, the Arab casualties being mostly at the hands of British security forces. A royal commission of inquiry under the aegis of Sir Walter Shaw attributed the clashes to the fact that “the Arabs have come to see in Jewish immigration not only a menace to their livelihood but a possible overlord of the future.” A second royal commission, headed by Sir John Hope Simpson, issued a report stating that there was at that time no margin of land available for agricultural settlement by new immigrants. These two reports raised in an acute form the question of where Britain’s duty lay if its specific obligations to the Zionists under the Balfour Declaration clashed with its general obligations to the Arabs under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. They also formed the basis of the Passfield White Paper, issued in October 1930, which accorded some priority to Britain’s obligations to the Arabs. Not only did it call for a halt to Jewish immigration, but it also recommended that land be sold only to landless Arabs and that the determination of “economic absorptive capacity” be based on levels of Arab as well as Jewish unemployment. This was seen by the Zionists as cutting at the root of their program, for, if the right of the Arab resident were to gain priority over that of the Jewish immigrant, whether actual or potential, development of the Jewish national home would come to a standstill. In response to protests from Palestinian Jews and London Zionists, the British prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, in February 1931 addressed an explanatory letter to Chaim Weizmann nullifying the Passfield White Paper, which virtually meant a return to the policy of the 1922 White Paper. This letter convinced the Arabs that recommendations in their favour made in Palestine could be annulled by Zionist influence at the centre of power in London. In December 1931 a Muslim congress at Jerusalem was attended by delegates from 22 countries to warn against the danger of Zionism.

From the early 1930s onward, developments in Europe once again began to impose themselves more forcefully on Palestine. The Nazi accession to power in Germany in 1933 and the widespread persecution of Jews throughout central and eastern Europe gave a great impetus to Jewish immigration, which jumped to 30,000 in 1933, 42,000 in 1934, and 61,000 in 1935. By 1936 the Jewish population of Palestine had reached almost 400,000, or one-third of the total. This new wave of immigration provoked major acts of violence against Jews and the British in 1933 and 1935. The Arab population of Palestine also grew rapidly, largely by natural increase, although some Arabs were attracted from outside the region by the capital infusion brought by middle-class Jewish immigrants and British public works. Most of the Arabs (nearly nine-tenths) continued to be employed in agriculture despite deteriorating economic conditions. By the mid-1930s, however, many landless Arabs had joined the expanding Arab proletariat working in the construction trades on the edge of rapidly growing urban centres. This was the beginning of a shift in the foundations of Palestinian economic and social life that was to have profound immediate and long-term effects. In November 1935 the Arab political parties collectively demanded that Jewish immigration cease, land transfer be prohibited, and democratic institutions be established. A boycott of Zionist and British goods was proclaimed. In December the British administration offered to set up a legislative council of 28 members, in which the Arabs (both Muslim and Christian) would have a majority. The British would retain control through their selection of nonelected members. Although Arabs would not be represented in the council in proportion to their numbers, Arab leaders favoured the proposal, but the Zionists criticized it bitterly as an attempt to freeze the national home through a constitutional Arab stranglehold. In any event, London rejected the proposal. This, together with the example of rising nationalism in neighbouring Egypt and Syria, increasing unemployment in Palestine, and a poor citrus harvest, touched off a long-smoldering Arab rebellion.

The Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt of 1936–39 was the first sustained violent uprising of Palestinian Arabs in more than a century. Thousands of Arabs from all classes were mobilized, and nationalistic sentiment was fanned in the Arabic press, schools, and literary circles. The British, taken aback by the extent and intensity of the revolt, shipped more than 20,000 troops into Palestine, and by 1939 the Zionists had armed more than 15,000 Jews in their own nationalist movement.

The revolt began with spontaneous acts of violence committed by the religiously and nationalistically motivated followers of Sheikh ʿIzz al-Dīn al-Qassām, who had been killed by the British in 1935. In April 1936 the murder of two Jews led to escalating violence, and Qassāmite groups initiated a general strike in Jaffa and Nablus. At that point the Arab political parties formed an Arab Higher Committee presided over by the mufti of Jerusalem, Amīn al-Ḥusaynī. It called for a general strike, nonpayment of taxes, and the closing of municipal governments (although government employees were allowed to stay at work) and demanded an end to Jewish immigration, a ban on land sales to Jews, and national independence. Simultaneously with the strike, Arab rebels, joined by volunteers from neighbouring Arab countries, took to the hills, attacking Jewish settlements and British installations in the northern part of the country. By the end of the year, the movement had assumed the dimensions of a national revolt, the mainstay of which was the Arab peasantry. Even though the arrival of British troops restored some semblance of order, the armed rebellion, arson, bombings, and assassinations continued.

A royal commission of inquiry presided over by Lord Robert Peel, which was sent to investigate the volatile situation, reported in July 1937 that the revolt was caused by Arab desire for independence and fear of the Jewish national home. The Peel Commission declared the mandate unworkable and Britain’s obligations to Arabs and Jews mutually irreconcilable. In the face of what it described as “right against right,” the commission recommended that the region be partitioned. The Zionist attitude toward partition, though ambivalent, was overall one of cautious acceptance. For the first time a British official body explicitly spoke of a Jewish state. The commission not only allotted to this state an area that was immensely larger than the existing Jewish landholdings but recommended the forcible transfer of the Arab population from the proposed Jewish state. The Zionists, however, still needed mandatory protection for their further development and left the door open for an undivided Palestine. The Arabs were horrified by the idea of dismembering the region and particularly by the suggestion that they be forcibly transferred (to Transjordan). As a result, the momentum of the revolt increased during 1937 and 1938.

In September 1937 the British were forced to declare martial law. The Arab Higher Committee was dissolved, and many officials of the Supreme Muslim Council and other organizations were arrested. The mufti fled to Lebanon and then Iraq, never to return to an undivided Palestine. Although the Arab Revolt continued well into 1939, high casualty rates and firm British measures gradually eroded its strength. According to some estimates, more than 5,000 Arabs were killed, 15,000 wounded, and 5,600 imprisoned during the revolt. Although it signified the birth of a national identity, the revolt was unsuccessful in many ways. The general strike, which was called off in October 1939, had encouraged Zionist self-reliance, and the Arabs of Palestine were unable to recover from their sustained effort of defying the British administration. Their traditional leaders were either killed, arrested, or deported, leaving the dispirited and disarmed population divided along urban-rural, class, clan, and religious lines. The Zionists, on the other hand, were united behind Ben-Gurion, and the Haganah had been given permission to arm itself. It cooperated with British forces and the Irgun Zvai Leumi in attacks against Arabs.

However, the prospect of war in Europe alarmed the British government and caused it to reassess its policy in Palestine. If Britain went to war, it could not afford to face Arab hostility in Palestine and in neighbouring countries. The Woodhead Commission, under Sir John Woodhead, was set up to examine the practicality of partition. In November 1938 it recommended against the Peel Commission’s plan—largely on the ground that the number of Arabs in the proposed Jewish state would be almost equal to the number of Jews—and put forward alternative proposals drastically reducing the area of the Jewish state and limiting the sovereignty of the proposed states. This was unacceptable to both Arabs and Jews. Seeking to find a solution acceptable to both parties, the British announced the impracticability of partition and called for a roundtable conference in London.

No agreement was reached at the London conference held during February and March 1939. In May 1939, however, the British government issued a White Paper, which essentially yielded to Arab demands. It stated that the Jewish national home should be established within an independent Palestinian state. During the next five years 75,000 Jews would be allowed into the country; thereafter Jewish immigration would be subject to Arab “acquiescence.” Land transfer to Jews would be allowed only in certain areas in Palestine, and an independent Palestinian state would be considered within 10 years. The Arabs, although in favour of the new policy, rejected the White Paper, largely because they mistrusted the British government and opposed a provision contained in the paper for extending the mandate beyond the 10-year period. The Zionists were shocked and enraged by the paper, which they considered a death blow to their program and to Jews who desperately sought refuge in Palestine from the growing persecution they were enduring in Europe. The 1939 White Paper marked the end of the Anglo-Zionist entente.

Progress toward a Jewish national home had, however, been remarkable since 1918. Although the majority of the Jewish population was urban, the number of rural Zionist colonies had increased from 47 to about 200. Between 1922 and 1940 Jewish landholdings had risen from about 148,500 to 383,500 acres (about 60,100 to 155,200 hectares) and now constituted roughly one-seventh of the cultivatable land, and the Jewish population had grown from 83,790 to some 467,000, or nearly one-third of a total population of about 1,528,000. Tel Aviv had developed into an all-Jewish city of 150,000 inhabitants, and hundreds of millions of dollars of Jewish capital had been introduced into the region. The Jewish literacy rate was high, schools were expanding, and the Hebrew language had become widespread. Despite a split in 1935 between the mainline Zionists and the radical Revisionists, who advocated the use of force to establish the Zionist state, Zionist institutions in Palestine became stronger in the 1930s and helped create the preconditions for the establishment of a Jewish state.

World War II

With the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Zionist and British policies came into direct conflict. Throughout the war Zionists sought with growing urgency to increase Jewish immigration to Palestine, while the British sought to prevent such immigration, regarding it as illegal and a threat to the stability of a region essential to the war effort. Ben-Gurion declared on behalf of the Jewish Agency: “We shall fight [beside Great Britain in] this war as if there was no White Paper and we shall fight the White Paper as if there was no war.” British attempts to prevent Jewish immigration to Palestine in the face of the Holocaust—the terrible tragedy befalling European Jewry and others deemed undesirable by the Nazis—led to the disastrous sinking of two ships carrying Jewish refugees, the Patria (November 1940) and the Struma (February 1942). In response, the Irgun, under the leadership of Menachem Begin, and a small terrorist splinter group, LEHI (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel), known for its founder as the Stern Gang, embarked on widespread attacks on the British, culminating in the murder of Lord Moyne, British minister of state, by two LEHI members in Cairo in November 1944.

During the war years the Jewish community in Palestine was vastly strengthened. Its moderate wing supported the British; in September 1944 a Jewish brigade was formed—a total of 27,000 Jews having enlisted in the British forces—and attached to the British 8th Army. Jewish industry in general was given immense impetus by the war, and a Jewish munitions industry developed to manufacture antitank mines for the British forces. For the Yishuv the war and the Holocaust confirmed that a Jewish state must be established in Palestine. Important also was the support of American Zionists. In May 1942, at a Zionist conference held at the Biltmore Hotel in New York City, Ben-Gurion gained support for a program demanding unrestricted immigration, a Jewish army, and the establishment of Palestine as a Jewish commonwealth.

The Arabs of Palestine remained largely quiescent throughout the war. Amīn al-Ḥusaynī had fled—by way of Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Italy—to Germany, whence he broadcast appeals to his fellow Arabs to ally with the Axis powers against Britain and Zionism. Yet the mufti failed to rally Palestinian Arabs to the Axis cause. Although some supported Germany, the majority supported the Allies, and approximately 23,000 Arabs enlisted in the British forces (especially in the Arab Legion). Increases in agricultural prices benefited the Arab peasants, who began to pay accumulated debts. However, the Arab Revolt had ruined many Arab merchants and importers, and British war activities, although bringing new levels of prosperity, further weakened the traditional social institutions—the family and village—by fostering a large urban Arab working class.

The Allied discovery of the Nazi extermination camps at the end of World War II and the undecided future of Holocaust survivors led to an increasing number of pro-Zionist statements from U.S. politicians. In August 1945 U.S. President Harry S. Truman requested that British Prime Minister Clement Attlee facilitate the immediate admission of 100,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors into Palestine, and in December the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives asked for unrestricted Jewish immigration to the limit of the economic absorptive capacity of Palestine. Truman’s request signaled the U.S. entry into the arena of powers determining the future of Palestine. The question of Palestine, now linked with the fate of Holocaust survivors, became once again the focus of international attention.

As the war came to an end, the neighbouring Arab countries began to take a more direct interest in Palestine. In October 1944 Arab heads of state met in Alexandria, Egypt, and issued a statement, the Alexandria Protocol, setting out the Arab position. They made clear that, although they regretted the bitter fate inflicted upon European Jewry by European dictatorships, the issue of European Jewish survivors ought not to be confused with Zionism. Solving the problem of European Jewry, they asserted, should not be achieved by inflicting injustice on Palestinian Arabs. The covenant of the League of Arab States, or Arab League, formed in March 1945, contained an annex emphasizing the Arab character of Palestine. The Arab League appointed an Arab Higher Executive for Palestine (the Arab Higher Committee), which included a broad spectrum of Palestinian leaders, to speak for the Palestinian Arabs. In December 1945 the league declared a boycott of Zionist goods. The pattern of the postwar struggle for Palestine was unmistakably emerging.

The early postwar period

The major issue between 1945 and 1948 was, as it had been throughout the mandate, Jewish immigration to Palestine. The Yishuv was determined to remove all restrictions to Jewish immigration and to establish a Jewish state. The Arabs were determined that no more Jews should arrive and that Palestine should achieve independence as an Arab state. The primary goal of British policy following World War II was to secure British strategic interests in the Middle East and Asia. Because the cooperation of the Arab states was considered essential to this goal, British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin opposed Jewish immigration and the foundation of an independent Jewish state in Palestine. The U.S. State Department basically supported the British position, but Truman was determined to ensure that Jews displaced by the war were permitted to enter Palestine. The issue was resolved in 1948 when the British mandate collapsed under the pressure of force and diplomacy.

In November 1945, in an effort to secure American coresponsibility for a Palestinian policy, Bevin announced the formation of an Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. Pending the report of the committee, Jewish immigration would continue at the rate of 1,500 persons per month above the 75,000 limit set by the 1939 White Paper. A plan of provincial autonomy for Arabs and Jews was worked out in an Anglo-American conference in 1946 and became the basis for discussions in London between Great Britain and the representatives of Arabs and Zionists.

In the meantime, Zionist pressure in Palestine was intensified by the unauthorized immigration of refugees on a hitherto unprecedented scale and by closely coordinated attacks by Zionist underground forces. Jewish immigration was impelled by the burning memories of the Holocaust, the chaotic postwar conditions in Europe, and the growing possibility of attaining a Jewish state where the victims of persecution could guarantee their own safety. The underground’s attacks culminated in Jerusalem on July 22, 1946, when the Irgun blew up a part of the King David Hotel containing British government and military offices, with the loss of 91 lives.

On the Arab side, a meeting of the Arab states took place in June 1946 at Blūdān, Syria, at which secret resolutions were adopted threatening British and American interests in the Middle East if Arab rights were disregarded. In Palestine the Ḥusaynīs consolidated their power, despite widespread mistrust of the mufti, who now resided in Egypt.

While Zionists pressed ahead with immigration and attacks on the government, and Arab states mobilized in response, British resolve to remain in the Middle East was collapsing. World War II had left Britain victorious but exhausted. After the war it lacked the funds and political will to maintain control of colonial possessions that were agitating, with increasing violence, for independence. When a conference called in London in February 1947 failed to resolve the impasse, Great Britain, already negotiating its withdrawal from India and eager to decrease its costly military presence in Palestine (of the more than 280,000 troops stationed there during the war, more than 80,000 still remained), referred the Palestine question to the United Nations (UN).

.

On August 31, 1947, a majority report of the UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) recommended that the region be partitioned into an Arab and a Jewish state, which, however, should retain an economic union. Jerusalem and its environs were to be international. These recommendations were substantially adopted by a two-thirds majority of the UN General Assembly in Resolution 181, dated November 29, 1947, a decision made possible partly because of an agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union on partition and partly because pressure was exerted on some small countries by Zionist sympathizers in the United States. All the Islamic Asian countries voted against partition, and an Arab proposal to query the International Court of Justice on the competence of the General Assembly to partition a country against the wishes of the majority of its inhabitants (in 1946 there were 1,269,000 Arabs and 678,000 Jews in Palestine) was narrowly defeated.

The Zionists welcomed the partition proposal both because it recognized a Jewish state and because it allotted slightly more than half of (west-of-Jordan) Palestine to it. As in 1937, the Arabs fiercely opposed partition both in principle and because nearly half of the population of the Jewish state would be Arab. Resolution 181 called for the formation of the UN Palestine Commission—which it tasked with selecting and overseeing provisional councils of government for the Jewish and Arab states by April 1, 1948—and set the date for the termination of the mandate no later than August 1, 1948. (The British later announced that the mandate would be terminated on May 15, 1948.)

Civil war in Palestine

Soon after the UN resolution, fighting broke out in Palestine. The Zionists mobilized their forces and redoubled their efforts to bring in immigrants. In December 1947 the Arab League pledged its support to the Palestinian Arabs and organized a force of 3,000 volunteers. Civil war spread, and external intervention increased as the disintegration of the British administration progressed.

Alarmed by the continued fighting, the United States in early March 1948 expressed its opposition to forcibly implementing a partition. A March 12 report by the UN Palestine Commission stated that the establishment of provisional councils of government able to fulfill their functions would be impossible by April 1. Arab resistance to the partition in principle precluded the establishment of an Arab council, and, although steps had been taken toward the selection of the Jewish council, the commission reported that the latter council would be unable to carry out its functions as intended by the resolution. Hampering efforts altogether was Great Britain’s refusal in any case to share with the commission the administration of Palestine during the transitional period. On March 19 the United States called for the UN Palestine Commission to suspend its efforts. On March 30 the United States proposed that a truce be declared and that the problem be further considered by the General Assembly.

The Zionists, insisting that partition was binding and anxious about the change in U.S. policy, made a major effort to establish their state. They launched two offensives during April. The success of these operations coincided roughly with the failure of an Arab attack on the Zionist settlement of Mishmar Ha ʿEmeq; the death in battle of an Arab national hero, ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Ḥusaynī, in command of the Jerusalem front; and the massacre, by Irgunists and members of the Stern Gang, of civilian inhabitants of the Arab village of Deir Yassin. On April 22 Haifa fell to the Zionists, and Jaffa, after severe mortar shelling, surrendered to them on May 13. Simultaneously with their military offensives, the Zionists launched a campaign of psychological warfare. The Arabs of Palestine, divided, badly led, and reliant on the regular armies of the Arab states, became demoralized, and their efforts to prevent partition collapsed.

On May 14 the last British high commissioner, General Sir Alan Cunningham, left Palestine. On the same day the State of Israel was declared and within a few hours won de facto recognition from the United States and de jure recognition from the Soviet Union. Early on May 15 units of the regular armies of Syria, Transjordan, Iraq, and Egypt crossed the frontiers of Palestine.

In a series of campaigns alternating with truces between May and December 1948, the Arab units were routed, and by the summer of 1949 Israel had concluded armistices with its neighbours. It had also been recognized by more than 50 governments throughout the world, joined the United Nations, and established its sovereignty over about 8,000 square miles (21,000 square km) of formerly mandated Palestine west of the Jordan River. The remaining 2,000 square miles (5,200 square km) were divided between Transjordan and Egypt. Transjordan retained the lands on the west bank of the Jordan River, including the eastern portion of Jerusalem (East Jerusalem), although its annexation of those lands in 1950 was not generally recognized as legitimate. In 1949 the name of the expanded country was changed to the Hashimite Kingdom of Jordan. Egypt retained control of, but did not annex, a small area on the Mediterranean coast that became known as the Gaza Strip. The Palestinian Arab community ceased to exist as a cohesive social and political entity.

Walid Ahmed KhalidiIan J. BickertonRashid Ismail KhalidiThe Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Palestine and the Palestinians (1948–67)

The partition of Palestine and its aftermath

If one chief theme in the post-1948 pattern was embattled Israel and a second the hostility of its Arab neighbours, a third was the plight of the huge number of Arab refugees. The violent birth of Israel led to a major displacement of the Arab population, who either were driven out by Zionist military forces before May 15, 1948, or by the Israeli army after that date or fled for fear of violence by these forces. Many wealthy merchants and leading urban notables from Jaffa, Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem fled to Lebanon, Egypt, and Jordan, while the middle class tended to move to all-Arab towns such as Nablus and Nazareth. The majority of fellahin ended up in refugee camps. More than 400 Arab villages disappeared, and Arab life in the coastal cities (especially Jaffa and Haifa) virtually disintegrated. The centre of Palestinian life shifted to the Arab towns of the hilly eastern portion of the region—which was immediately west of the Jordan River and came to be called the West Bank.

Like everything else in the Arab-Israeli conflict, population figures are hotly disputed. Nearly 1,400,000 Arabs lived in Palestine when the war broke out. Estimates of the number of Arabs displaced from their original homes, villages, and neighbourhoods during the period from December 1947 to January 1949 range from about 520,000 to about 1,000,000; there is general consensus, however, that the actual number was more than 600,000 and likely exceeded 700,000. Some 276,000 moved to the West Bank; by 1949 more than half the prewar Arab population of Palestine lived in the West Bank (from 400,000 in 1947 to more than 700,000). Between 160,000 and 190,000 fled to the Gaza Strip. More than one-fifth of Palestinian Arabs left Palestine altogether. About 100,000 of these went to Lebanon, 100,000 to Jordan, between 75,000 and 90,000 to Syria, 7,000 to 10,000 to Egypt, and 4,000 to Iraq.

The term “Palestinian”

Henceforth the term Palestinian will be used when referring to the Arabs of the former mandated Palestine, excluding Israel. Although the Arabs of Palestine had been creating and developing a Palestinian identity for about 200 years, the idea that Palestinians form a distinct people is relatively recent. The Arabs living in Palestine had never had a separate state. Until the establishment of Israel, the term Palestinian was used by Jews and foreigners to describe the inhabitants of Palestine and had only begun to be used by the Arabs themselves at the turn of the 20th century. With the Arab world in a period of renaissance popularizing notions of Arab unity and nationalism amid the decline of the Ottoman Empire, most saw themselves as part of the larger Arab or Muslim community. The Arabs of Palestine began widely using the term Palestinian starting in the pre-World War I period to indicate the nationalist concept of a Palestinian people. But after 1948—and even more so after 1967—for Palestinians themselves the term came to signify not only a place of origin but, more importantly, a sense of a shared past and future in the form of a Palestinian state.

Diverging histories for Palestinian Arabs

Palestinian citizens of Israel

Approximately 150,000 Arabs remained in Israel when the Israeli state was founded. This group represented about one-eighth of all Palestinians and by 1952 roughly the same proportion of the Israeli population. The majority of them lived in villages in western Galilee. Because much of their land was confiscated, Arabs were forced to abandon agriculture and become unskilled wage labourers, working in Jewish industries and construction companies. As citizens of the State of Israel, in theory they were guaranteed equal religious and civil rights with Jews. In reality, however, until 1966 they lived under a military jurisdiction that imposed severe restrictions on their political options and freedom of movement. Most of them remained politically quiescent, and many acquiesced to the reality of an Israel governed according to the ideology of Zionism. Many also sought to ameliorate their circumstances through electoral participation, education, and economic integration.

Israel sought to impede the development of a cohesive national consciousness among the Palestinians by dealing with various minority groups, such as Druze, Circassians, and Bedouin; by hindering the work of the Muslim religious organizations; by arresting and harassing individuals suspected of harbouring nationalist sentiments; and by focusing on education as a means of creating a new Israeli Arab identity. By the late 1960s, as agriculture declined and social customs related to such events as bride selection and marriage broke down, the old patriarchal clan system had all but collapsed. For almost 20 years after Israel was established, Palestinian citizens of Israel were isolated from other Arabs.

West Bank (and Jordanian) Palestinians

The Jordanian monarchy saw in the events of 1948–49 the opportunity to expand Jordanian territory and to integrate Palestinians into its population and thereby create a new inclusive Jordanian nationality. Through a series of political and social policies, Jordan sought to consolidate its control over the political future of Palestinians and to become their speaker. It provided education and, in 1949, extended citizenship to Palestinians; indeed, a majority of all Palestinians became Jordanian citizens. However, tensions soon developed between original Jordanian citizens and the better-educated, more skilled newcomers. Wealthy Palestinians lived in the towns of the eastern and western sides of the Jordan River, competing for positions within the government, while the fellahin filled the UN refugee camps.

Palestinians constituted about two-thirds of the population of Jordan. Half the seats in the Jordanian Chamber of Deputies were reserved for representatives from the West Bank, but this measure and similar attempts to integrate the West Bank with the area lying east of the Jordan River were made difficult by the significant social, economic, educational, and political differences between the residents of each. Jordanian Palestinians, other than the notable families favoured by the Jordanian monarchy, tended to support the radical pan-Arab and anti-Israeli policies of Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser rather than the more cautious and conciliatory position of Jordan’s King Ḥussein.

Palestinians in the Gaza Strip

During the 20 years the Gaza Strip was under Egyptian control (1948–67), it remained little more than a reservation. Egyptian rule was generally repressive. Palestinians living in the region were denied citizenship, which rendered them stateless (i.e., it left them without citizenship of any nation), and they were allowed little real control over local administration. They were, however, allowed to attend Egyptian universities and, at times, to elect local officials.

In 1948 Amīn al-Ḥusaynī declared a Government of All Palestine in the Gaza Strip. However, because it was totally dependent on Egypt, it was short-lived. The failure of this venture and al-Ḥusaynī’s lack of credibility because of his collaboration with the Axis powers during World War II did much to weaken Palestinian Arab nationalism in the 1950s.

The Gaza Strip, 25 miles (40 km) long and 4–5 miles (6–8 km) wide, became one of the most densely populated areas of the world, with more than four-fifths of its population urban. Poverty and social misery became characteristic of life in the region. The rate of unemployment was high; many of the Palestinians lived in refugee camps, depending primarily on UN aid (see below). Most of the agricultural lands they had formerly worked were now inaccessible, and little or no industry was allowed, but commerce flourished as Gaza became a kind of duty-free port for Egyptians. Although some Gaza Strip Palestinians were able to leave the territory and gain an education and find employment elsewhere, most had no alternative but to stay in the area, despite its lack of natural resources and jobs.

The UNRWA camps

In December 1949 the UN General Assembly created the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) to assist the Palestinian refugees. In May 1950 UNRWA established a total of 53 refugee “camps” on both sides of the Jordan River and in the Gaza Strip, Lebanon, and Syria to assist the 650,000 or more Arab refugees it calculated needed help. Initially refugees in the improvised camps lived in tents, but after 1958 these were replaced by small houses of concrete blocks with iron roofs. Conditions were extremely harsh; often several families had to share one tent, and exposure to the extreme winter and summer temperatures inflicted additional suffering. Loss of home and income lowered morale. Although the refugees were provided with rent-free accommodations and basic services such as water, health care, and education (UNRWA ran both elementary and secondary schools in the camps, teaching more than 40,000 students by 1951), poverty and misery were widespread. Work was scarce, even though UNRWA sought to integrate the Palestinians into the depressed economies of the “host” countries.

Palestinians who continued to live in refugee camps felt a greater sense of alienation and dislocation than the more fortunate ones who found jobs and housing and became integrated into the national economies of the countries in which they resided. Although the camps strengthened family and village ties, their demoralized inhabitants were isolated from mainstream Palestinian political activities during the 1950s.

Palestinians outside mandated Palestine

Palestinians found employment in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and the Persian Gulf states, but only a few were able to become citizens of those countries. Often they were the victims of discrimination, as well as being closely supervised by the respective governments intent on limiting their political activities.

Resurgence of Palestinian identity

The events of 1948 (also called by Palestinians al-nakbah, “the catastrophe”) and the experience of exile shaped Palestinian political and cultural activity for the next generation. The central task of reconstruction fell to Palestinians living outside Israel—both in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip communities and in the new Palestinian communities outside the former British mandate. (Palestinians living within the State of Israel remained in an ambiguous isolated situation and were regarded with some suspicion by both Israelis and other Palestinians.) The new leaders came disproportionately from among those who had moved to various Middle Eastern states and to the West, even though four out of five Palestinians had remained within the borders of the former British mandate. By the mid-1960s, despite Israeli efforts to forestall the emergence of a renewed Palestinian identity, a young educated leadership had arisen, replacing the discredited traditional local and clan leaders.

The role of camps

Palestinian refugee camps differed depending on the country in which they were located, but they shared one common development—the emergence of a “diaspora consciousness.” In time this consciousness grew into a renewed national identity and reinvigorated social institutions, leading to the establishment of more complex social and political structures by the 1960s. A new Palestinian leadership emerged from the schools UNRWA had established, as well as from the universities of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, western Europe, and the United States. Palestinians living in the UNRWA-administered refugee camps felt isolated, politically powerless, disoriented, bitter, and resentful. They remained unassimilated and were generating a new sense of identity based on a pan-Arabism inspired by Nasser, the cultivated memory of a lost paradise (Palestine), and an emerging pan-Islamic movement.

The role of Palestinians outside formerly mandated Palestine

By the late 1960s a class of educated and mobile Palestinians had emerged, with fewer than half of them living in the West Bank or Gaza. They were working in the oil companies, civil services, and educational institutions of most Arab states in the Middle East. Having successfully resisted the efforts of Amīn al-Ḥusaynī, Jordan, and Egypt to control and speak for them, they joined the process of reshaping Palestinian consciousness and institutions. Thus Palestinians entered a new stage of the struggle for nationhood.

The Palestine Liberation Organization

An Arab summit meeting in Cairo in 1964 led to the formation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). A political umbrella organization of several Palestinian groups, the PLO thereafter consistently claimed to be the sole representative of all Palestinian people. Its first leader was Aḥmad Shuqayrī, a protégé of Egypt. In its 1968 charter (the Palestine National Charter, or Covenant) the PLO delineated its basic principles and goals, the most important of which were the right to an independent state, the total liberation of Palestine, and the destruction of the State of Israel.

A Palestine National Council (PNC) was established to serve as the supreme body, or parliament, of the PLO, and an executive committee was formed to manage PLO activities. Initially, the PNC consisted of civilian representatives from various areas, including Jordan, the West Bank, and the Persian Gulf states, but representatives of guerrilla organizations were added in 1968.

Fatah and other guerrilla organizations

Several years before the creation of the PLO, a secret organization had been formed: the Palestine National Liberation Movement (Ḥarakat al-Taḥrīr al-Waṭanī al-Filasṭīnī), known from a reversal of its Arabic initials as Fatah. Both the PLO and Fatah undertook the training of guerrilla units for raids on Israel. In addition to Fatah, the largest and most influential guerrilla organization, several others emerged in the late 1960s. The most important ones were the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine–General Command (PFLP–GC, a splinter group from the PFLP), and al-Ṣāʿiqah (backed by Syria). These groups joined forces inside the PLO despite their differences in ideology and tactics (some were dedicated to openly terrorist tactics). In 1969 Yasser Arafat, leader of Fatah, became chairman of the PLO’s executive committee and thus the chief of the Palestinian national movement.

Despite their differences in tactics and ideology, the guerrilla organizations were united in rejecting any political settlement that did not include what they characterized as the total liberation of Palestine and the return of the refugees to their homeland, goals that were to be achieved through armed struggle. Palestinian spokesmen claimed, however, that, while they aimed at dismantling Israel and purging Palestine of Zionism, they also sought to establish a nonsectarian state in which Jews, Christians, and Muslims could live in equality. Most Israelis doubted the sincerity or practicality of this goal and viewed the PLO as a terrorist organization committed to destroying not only the Zionist state but Israeli Jews.

The Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and its consequences

In the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 (also known as the Six-Day War), Israel defeated the combined forces of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan and also overran large tracts of territory, including East Jerusalem, the West Bank (known to Israelis by the biblical names Judaea and Samaria), and the Gaza Strip. Israel’s victory gave rise to another exodus of Palestinians, with more than 250,000 people fleeing to the eastern bank of the Jordan River. However, roughly 600,000 Palestinians remained in the West Bank and 300,000 in the Gaza Strip. Thus, the 3,000,000 Israeli Jews came to rule some 1,200,000 Arabs (including the 300,000 already living in the State of Israel). Moreover, a movement developed among Israelis who advocated settling the occupied territories—particularly the West Bank—as part of the Jewish patrimony in the Holy Land. Several thousand Israeli Jews settled in the territories in the decade following the war.

Palestinian citizens of Israel

In the years following the 1967 war, circumstances changed dramatically for Palestinian citizens of Israel. As a result of their resumed contact with the Palestinians of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, they began to recover from their long period of inactivity. Following the Yom Kippur War of 1973, Palestinians in Israel played a greater role in Israeli institutions. They also were significantly affected by Israel’s economic prosperity, and by the 1980s the economy of Palestinian areas had gained some autonomy, as Palestinians moved from unskilled work to business ownership.

The PLO’s rise as a revolutionary force

Throughout the 1970s and ’80s the PLO, dominated by Fatah, acted as a state in the making and launched frequent military attacks on Israel. The strategy of armed struggle had been inaugurated as early as the 1950s, and, indeed, guerrilla raids against military and civilian targets in Israel had been a factor leading to the Suez Crisis of 1956 and the 1967 war. However, after 1967 Fatah launched a new wave of violent activities, and the Palestinian guerrilla groups, under the umbrella of the PLO, emerged as an element of major importance in the Middle East. The Arab-Israeli war had discredited Nasser’s Pan-Arabism, and Fatah quickly permeated and mobilized the reunited Palestinian population, providing social services and organizations. One result was an escalating cycle of raids and reprisals between the Palestinian guerrillas and Israel; guerrilla attacks on Israeli occupation forces and terror attacks on Israeli civilians (defended by the PLO until renounced by Arafat in 1988) became a key element in the struggle against Israel.

The PLO’s struggle for Palestinian autonomy

Although generally recognized as the symbol of the Palestinian national movement, the PLO lacked organizational cohesion. It championed Palestinian distinctiveness and autonomy, but circumstances forced the leadership to remain somewhat distant from the lives of Palestinians. This made it difficult to impose a unified policy. A major problem for the PLO was gaining autonomy in order to pursue Palestinian interests, especially since the effort to do so inevitably brought the organization into conflict with the Arab states in which Palestinians lived.

Palestinians and the PLO in Jordan

Within Jordan an understanding was reached whereby the royal government allowed the Palestinian guerrillas independent control of their own bases in the Jordan Valley, but relations between the government and the guerrillas remained uneasy. The guerrillas suspected King Ḥussein—who had to face the damage inflicted upon his country by Israeli reprisals—of preparing to reach a direct settlement with Israel at their expense.

Tensions between the Jordanian army loyal to King Ḥussein and the Palestinian guerrillas erupted in a brief but bloody civil war in September 1970 that became known as “Black September.” On September 6–9 the PFLP hijacked to a Jordanian airstrip three airliners (American, Swiss, and British) with a total of more than 300 people aboard. The hijackers threatened to destroy the aircraft, with the passengers aboard, unless Palestinian guerrillas detained in Europe and Israel were released. All the passengers were freed by September 30, when the PFLP secured its main demands (after destroying the airliners). Full warfare ensued when the Jordanian army moved against the guerrillas.

By September 17 the army was fighting the guerrillas in Amman and in northern Jordan, where the guerrillas were reinforced by Syria-based armoured units of the Palestine Liberation Army—a body ostensibly part of the PLO but in fact controlled by Syria. Hostilities formally ended on September 25, with the guerrillas still in control of their northern strongholds. Total casualties were variously estimated at 1,000 to 5,000 people killed and up to 10,000 injured. In 1971, however, the fighting resumed, and the Jordanian army established full control over the whole country and crushed the Palestinian military. From that point on, the king and the PLO were deeply suspicious of each other, and the majority of Palestinians holding Jordanian citizenship, especially those living on the West Bank under Israeli control, became highly critical of the king and his policies.

Palestinians and the PLO in Lebanon

Driven from Jordan, the PLO intensified its activities in Lebanon. The presence of more than 235,000 Palestinians was a source of tension and conflict in Lebanon, as it had been in Jordan. Palestinians had few rights, and most worked for low wages in poor conditions. Palestinian guerrillas continued to carry out attacks against Israel. Israel countered with raids, primarily into southern Lebanon. The Lebanese government sought to restrict the activities of the Palestinian guerrillas, which led to sporadic fighting between the Lebanese army and the guerrillas.

In 1973 the Palestinian movement suffered a severe blow from an Israeli commando attack in Beirut in April that killed three of its leaders. Following the attack, the Lebanese army assaulted guerrilla bases and refugee camps throughout the country. An agreement was reached requiring the Palestinians to limit their activities to border areas near Israel and refugee camps near urban centres. After 1973 many Palestinians from Lebanon and Jordan moved to the increasingly prosperous and labour-hungry Arab oil states, such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

International recognition

The PLO made important gains in its international relations during the 1970s. By the end of the decade the organization had representatives in more than 80 countries. On September 22, 1974, the UN General Assembly, overriding strong Israeli objections, included on its agenda for the first time the “Palestine question” as a separate subject for debate rather than as part of the general question of the Middle East. On November 13 the assembly heard Arafat plead for the Palestinian people’s national rights.

International recognition of the PLO had important repercussions within the Arab camp. At an Arab summit conference held in Rabat, Morocco, on October 26–28, 1974, King Ḥussein accepted a resolution stating that any “liberated” Palestinian territory “should revert to its legitimate Palestinian owners under the leadership of the PLO.” The Rabat decision was denounced by the more radical “rejection front,” composed of the PFLP, the PFLP–GC, the pro-Iraq Arab Liberation Front, and the Front for the Popular Palestinian Struggle, which sought to regain all of Palestine. Although the decision was recognized as enhancing the less extreme position of the PLO elements led by Arafat, the United States continued adamantly to refuse to recognize or deal with the PLO so long as the PLO refused to recognize Israel’s right to exist.

Palestinians and the civil war in Lebanon

Palestinian guerrilla activity against Israel in 1975 was largely confined to the southern Lebanese border area, where it provoked heavy Israeli attacks from air, land, and sea against Palestinian refugee camps that the Israelis alleged were being used as guerrilla bases. Israeli raids, however, were overshadowed by growing civil strife in Lebanon that developed along Muslim-Christian lines. Civil war between the militias of Lebanon’s sectarian groups erupted in 1975, bringing 15 years of bloodshed, in which more than 100,000 people were killed. The presence of Palestinians was a factor contributing to the civil war, and the war proved disastrous for them.

The PLO initially tried to stay out of the fighting, but by the end of 1975 groups within the overall organization, particularly the “rejection front” groups, were being drawn into an alliance with the Muslim and leftist groups fighting against the Christians. Fighting broke out throughout the country during the first half of January 1976 as Christian forces, foremost the right-wing Maronite Phalange, blockaded the Palestinian refugee camps, and the Palestinian forces and their Lebanese allies responded by attacking Christian villages on the coast. Intense fighting continued, and the PLO, despite all efforts, proved unable to protect the Palestinian population. In August, after a two-month siege, Christian forces killed an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 Palestinians in the Tall al-Zaʿtar camp northeast of Beirut. A peace agreement was negotiated in October 1976. The settlement provided for the creation of a 30,000-member Arab Deterrent Force (ADF), a cease-fire throughout the country, withdrawal of forces to positions held before April 1975, and implementation of a 1969 agreement limiting Palestinian guerrilla operations in Lebanon.

Although the Palestinian guerrillas suffered heavy losses in the Lebanese civil war, they continued to mount attacks against Israel in the late 1970s. Israel again responded with raids into southern Lebanon. In September 1977 Israeli troops crossed into southern Lebanon to support right-wing Christian forces. On March 11, 1978, a Palestinian raid into Israel killed three dozen civilian tourists and wounded some 80 others, and Israel invaded southern Lebanon three days later (Operation Litani). On March 19 the UN Security Council passed resolution 425, calling for Israel to withdraw and establishing the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). The Israelis withdrew their forces only partially and continued to occupy a strip of Lebanese territory along the southern frontier, in violation of this resolution. They had been only partly successful in their aim of destroying Palestinian guerrillas and their bases south of the Litani River. Several hundred of the Palestinian guerrillas had been killed, but most of them had escaped northward. Estimates of civilian casualties ranged from 1,000 to 2,000.

The PLO in the occupied territories

Under the Likud Party government of the late 1970s and early ’80s, Israel’s settlements in the West Bank grew dramatically, as part of a new Likud policy to maintain strategic dominance in the area. The growth in settlements was accompanied by an increase in Israeli control over the territories, and large parts of those territories were incorporated into Israel’s infrastructure. As this occupation solidified, many local Palestinian leaders turned to building social organizations, labour unions, and religious, educational, and political institutions. The PLO responded by making its presence increasingly felt in the occupied territories, building its own youth groups, providing families with economic assistance, and putting in place a rival political infrastructure that made it possible for PLO-supported candidates to win in the municipal elections of 1976. By the early 1980s the PLO had set up an extensive bureaucratic structure that provided health, housing, educational, legal, media, and labour services for Palestinians both inside and outside the camps. Israeli and Jordanian attempts to encourage alternatives to the PLO failed in the 1980s. Active opposition to Israeli control in the West Bank spread, while frequent demonstrations, strikes, and other incidents occurred, particularly among students.

Negotiations, violence, and incipient self-rule

The late 1970s was a period of more active negotiation on Arab-Israeli disputes. The Arab states supported Palestinian participation in an overall settlement providing for Israeli withdrawal from areas occupied since the 1967 war and establishing a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The U.S. position toward the Palestinians showed signs of softening. In March 1977 U.S. President Jimmy Carter spoke of the need for a Palestinian homeland, and he later stated that it was essential for the Palestinians to take part in the peace process. The Israeli cabinet continued to reject the participation of the PLO in the peace process but agreed not to look too closely at the background of Palestinians who might become members of delegations from Arab countries.

The Camp David Accords and the PLO

In November 1977 the Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat, initiated peace negotiations that led to the agreement known as the Camp David Accords in September 1978 and to the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty signed on March 26, 1979. Provisions of the accords (named for Camp David, Maryland, U.S., where they were negotiated) included the establishment of a self-governing authority in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and a transitional period of not more than five years, at the end of which the inhabitants would become autonomous. The Soviet Union during the time of the peace negotiations recognized the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinians and in 1981 extended formal diplomatic recognition. The nations of western Europe announced their support of PLO participation in peace negotiations in June 1980. The PLO continued to seek diplomatic recognition from the United States, but the Carter administration honoured a secret commitment the former U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger made to Israel not to deal with the PLO so long as it declined to renounce terrorism and to recognize Israel’s right to exist.

The dispersal of the PLO from Lebanon

The Likud Party government of Israel viewed the possibility of peace and compromise with suspicion. On June 6, 1982, Israel, claiming that it intended to end attacks on its territory (although a cease-fire had been in effect since July 1981) and aiming to dislodge the PLO and encourage the installation of a Lebanese government friendly to Israel, launched an invasion of Lebanon. PLO and Syrian forces were defeated by Israeli troops, and the remaining PLO forces were contained in west Beirut. After a lengthy siege and bombardment by Israel in July and August 1982, some 11,000 Palestinian fighters were allowed to leave Beirut for various destinations, under international guarantees for their own safety and that of their civilian dependents. Despite these guarantees, however, after Israeli troops had occupied west Beirut, the Phalangists, Israel’s rightist Lebanese allies, were allowed by Israeli forces into the Beirut refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, where they massacred hundreds (estimates vary between 700 and 3,000) of Palestinian and Lebanese civilians.

Although not all PLO guerrillas were forced to leave Lebanon, the PLO infrastructure in the southern part of the country was destroyed, and Arafat’s departure from Beirut to northern Lebanon marked the effective end of the PLO’s military and political presence in the country. Ultimately, the new government of Lebanon came under the sway of Syria. The dispersal of the PLO from Lebanon significantly weakened the organization’s military strength and political militancy. It was unable to operate freely from any of the nations bordering Israel. Arafat and the other PLO leaders were also threatened by the emergence within Fatah of a faction encouraged by Syria. In December 1983 Arafat was driven out of northern Lebanon by the Syrians and their protégés inside the PLO.

After having established himself near Tunis, Tunisia, Arafat turned once again to diplomatic initiatives. He sought Egyptian and Jordanian support against Syria. He also looked to King Ḥussein as an intermediary for negotiations with the United States and Israel that might lead to a Palestinian ministate on the West Bank within a Jordan-Palestine confederation—an idea that had been favoured by the dominant factions in the PLO since the early 1980s. This policy was expressed most concretely in the meeting of the Palestine National Council in Amman in November 1984, the first time it had met there since Jordan had crushed the PLO armed forces in 1970.

Years of mounting violence

Violence escalated from the mid-1980s onward. Rejectionist elements within the PLO renewed their activities, attracting worldwide attention. In October 1985 members of the Palestine Liberation Front, a small faction within the PLO headed by Abū ʿAbbās, hijacked an Italian cruise ship, the Achille Lauro, and murdered one of its passengers. Following an Israeli bombing attack on PLO headquarters near Tunis several days before the hijacking, Arafat moved some departments to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Lebanese Shīʿite Muslim groups fought the PLO to stop its reemergence as an armed rival for supremacy in the chaotic situation prevalent in west Beirut and southern Lebanon. West Bank Palestinians demonstrated and engaged in strikes in late 1986.

In Israel several new developments strengthened Palestinian feelings of alienation from the Jewish majority. Jewish ultranationalists increased their demands for more Jewish settlements and the annexation of the West Bank and advocated the forceful removal of the Palestinian Arabs from the occupied territories. The Israeli parliament passed a bill in 1985 banning any political party that endangered state security—i.e., any party that was opposed to Zionism. This reinforced the feeling of most Palestinian citizens of Israel that no legal political party could adequately reflect their national, economic, and political views, although the only party actually banned was the anti-Arab Kach Party. Israelis—especially West Bank settlers—became more antagonistic and militant toward Palestinians as armed attacks against Israel and Israelis living abroad increased in number. Throughout 1986–87, attacks by Palestinians on Israeli settlers and by Israeli settlers on Palestinians mounted. By 1988 more than half of the land in the West Bank and about a third of the land in the Gaza Strip had been transferred to Jewish control, and the Israeli population of the West Bank—mostly concentrated in 15 metropolitan satellites of Tel Aviv–Yafo and Jerusalem—had reached about 100,000.

By the late 1980s a whole generation of Palestinian youth had grown up under Israeli occupation. Nearly three-fourths of Palestinians were younger than 25 years of age. Their political status was uncertain, their civil rights diminished, and their economic status low and dependent on Israel’s economy. Between 100,000 and 120,000 Palestinians crossed daily from the occupied territories into Israel to work. They did not have much faith in Arab governments, nor did they place strong trust in the PLO, which, although still a powerful symbol of Palestinian aspirations, had not succeeded by either diplomatic or military efforts to win Palestinian self-determination. Remittances to family members left behind from those hundreds of thousands who had migrated to Jordan and the Persian Gulf states for work in the 1960s and ’70s were reduced drastically as the economies of many Middle Eastern countries were hit by falling oil prices. Increasingly, Palestinians came to rely on their own efforts.

The first intifadah

When the Palestinians saw no improvement in effective support of their aspirations from other countries and no likely favourable change coming from the Israelis, they engaged, throughout 1987, in small-scale demonstrations, riots, and occasional violence directed against Israelis. The Israeli authorities responded with university closings, arrests, and deportations. Large-scale riots and demonstrations broke out in the Gaza Strip in early December and continued for more than five years thereafter. This uprising, which became known as the intifadah (Arabic: “shaking off”), inspired a new era in Palestinian mass mobilization. Masked young demonstrators turned to throwing stones at Israeli troops, and the soldiers responded by shooting and arresting them. Women, and women’s organizations, were prominent. The persistent disturbances, initially spontaneous, before long came under the leadership of the Unified National Command of the Uprising, which had links to the PLO. The PLO soon incorporated the Unified Command, but not before the local leaders had pushed Arafat to abandon formally his commitment to armed struggle and to accept Israel and the notion of a two-state solution to the conflict.

One group, Hamas—an acronym for the Islamic Resistance Movement—challenged the authority of the secular nationalist movement, especially inside Gaza, and sought to take over the leadership of the intifadah. Hamas was an underground offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, which had built up a network of religious, educational, and charitable institutions in the occupied territories, in addition to establishing an armed wing known as the Sheikh ʿIzz al-Dīn al-Qassām Brigades (named for the nationalist leader killed by the British in 1935). Hamas rejected any accommodation with Israel.

Tactics and tolls

The tactics of the intifadah were highly sophisticated. Union-organized strikes, commercial boycotts and closures, and demonstrations were carried out in one part of the territories, and then, after Israel had reestablished its local power there, they were transferred to a previously quiescent area. Palestinian refugee camps provided major centres for the resistance, but Palestinian Arabs living in more affluent circumstances also participated, and some Palestinian citizens of Israel showed their sympathy with the goals of the uprising. During its first year more than 300 Palestinians were killed, more than 11,500 wounded (nearly two-thirds of whom were under 15 years of age), and many more arrested. Israel closed universities and schools, destroyed houses, and imposed curfews—yet it was unable to quell the uprising. By mid-1990 the International Red Cross estimated that more than 800 Palestinians had been killed by Israeli security forces, more than 200 of whom were under the age of 16. Some 16,000 Palestinians were in prison. By contrast, fewer than 50 Israelis had been killed. Some hundreds of Palestinians in the occupied territories, accused of being collaborators with Israel, were killed by their compatriots. Political paralysis gripped Israel.

PLO declaration of independence

Arafat sought to establish himself as the only leader who could unite and speak for the Palestinians, and in mid-1988 he took the diplomatic initiative. At the 19th session of the PNC, held near Algiers on November 12–15, 1988, he succeeded in having the council issue a declaration of independence for a state of Palestine in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Arafat proclaimed the state (without defining its borders) on November 15. Within days more than 25 countries (including the Soviet Union and Egypt but excluding the United States and Israel) had extended recognition to the government-in-exile.

The final weeks of 1988 opened a new chapter in Palestinian-Israeli relations. In December Arafat announced that the PNC recognized Israel as a state in the region and condemned and rejected terrorism in all its forms—including state terrorism, the PLO’s term for Israel’s actions. He addressed a special meeting of the UN General Assembly convened at Geneva and proposed an international peace conference under UN auspices. He publicly accepted UN resolutions 242 and 338, thereby recognizing, at least implicitly, the State of Israel. Despite their ambiguities, UN resolution 242 (1967), which encapsulated the principle of land for peace, and resolution 338 (1973), which called for direct negotiations, were regarded by both parties as the starting points for negotiations. Although Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir stated that he was still not prepared to negotiate with the PLO, the U.S. government announced that it would open dialogue with the PLO.

The move toward self-rule

The Oslo Accords

The approaching end of the Cold War left the Palestinians diplomatically isolated, as did PLO support for Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, who had invaded Kuwait in August 1990 but was defeated by a U.S.-led alliance in the Persian Gulf War (1990–91). Funds from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the Persian Gulf states dried up. The Palestinian community in Kuwait, which had consisted of about 400,000 people, was reduced to a few thousand. Economic hardship was compounded by the fact that, during the continuing conflict along the Lebanese border and in the occupied territories, Israel imposed severe travel restrictions on Palestinian day labourers. The overall result was loss of jobs, loss of morale, and loss of support for the PLO leadership in Tunis.