Search Results

Featured snippet from the web

..Slavery and the British transatlantic slave trade

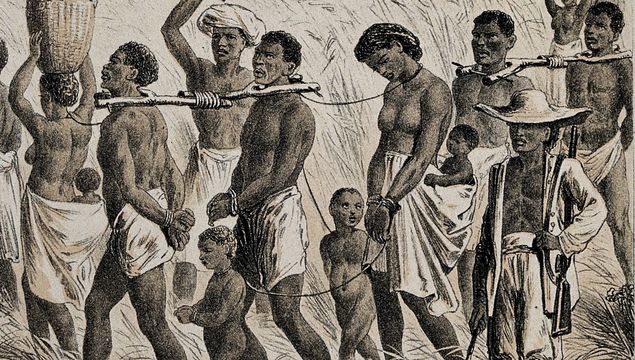

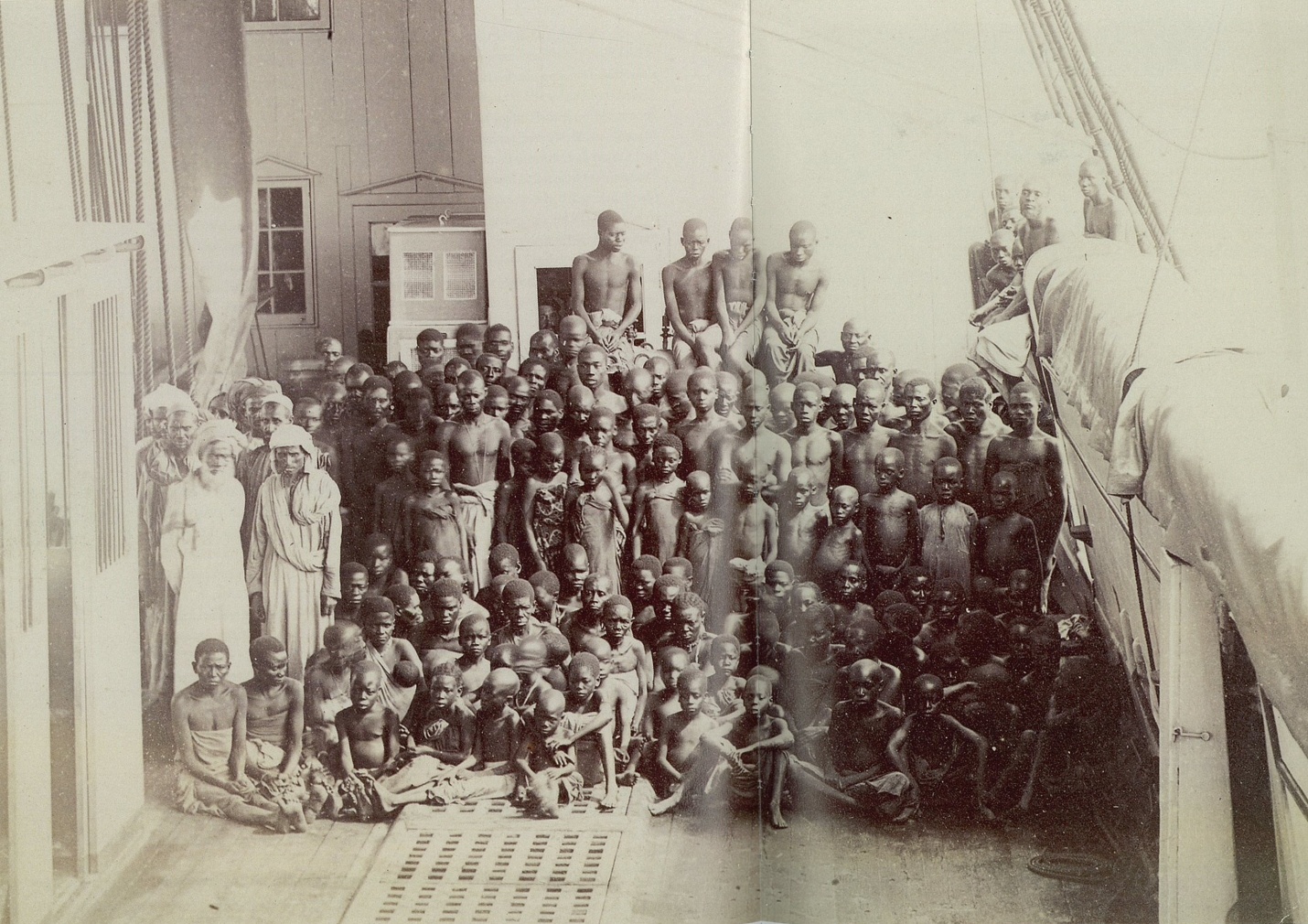

Men and women in Africa captured into slavery.Wellcome Images / Wiki

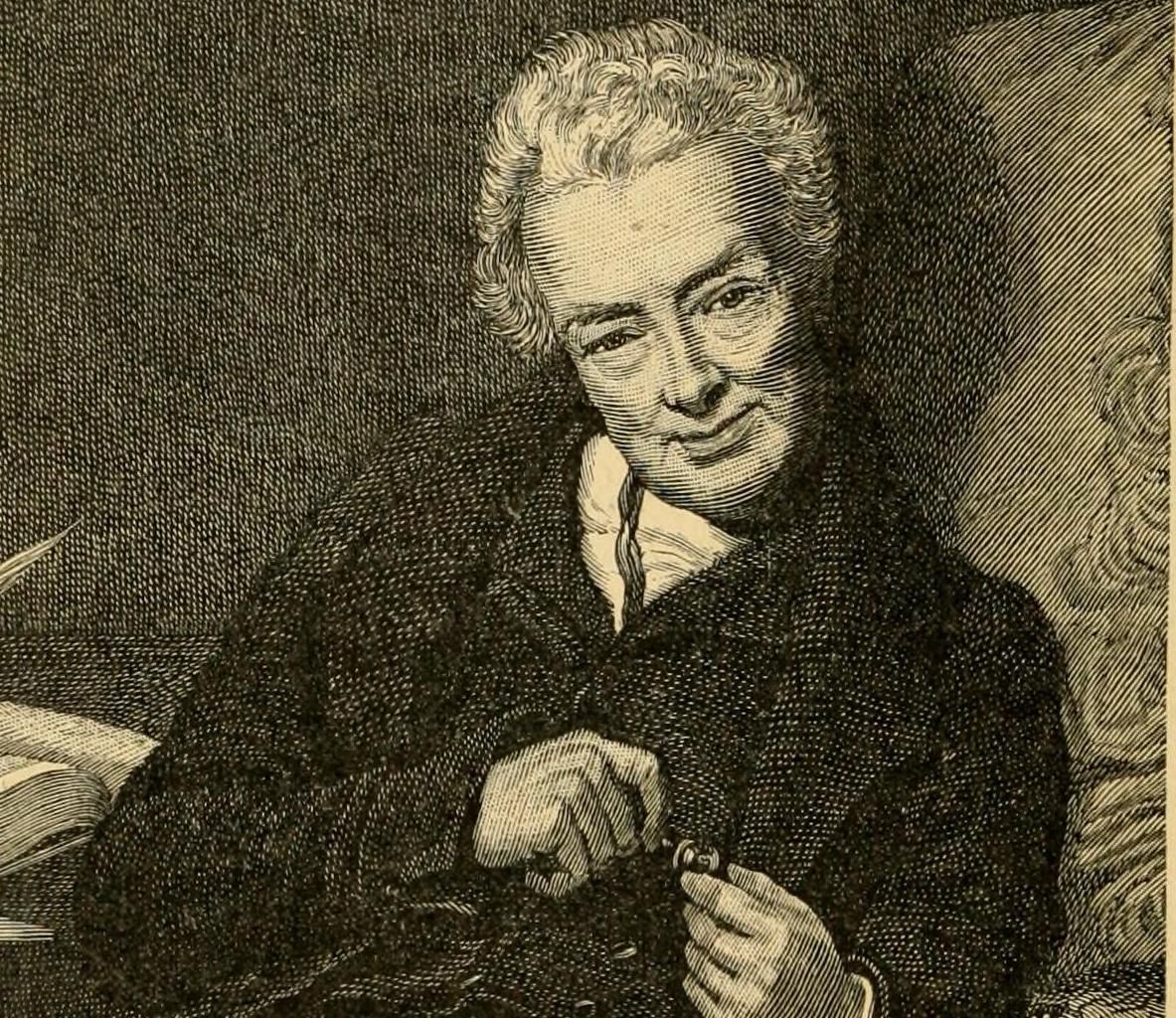

William Wilberforce, "The Saints" and the political events in Britain which led up to the abolition of slavery in 1833 across the British Empire.

It had been decades since the first mention of the issue in Parliament. In 1791, 163 Members of the Commons had voted against abolition. Very few MPs dared to defend the trade on moral grounds, even in the early debates. Instead, they called attention to the many economic and political reasons to continue it.

Those who profited from the trade made up a large vested interest, and everyone knew that an end to the slave trade also jeopardized the entire plantation system. “The property of the West Indians is at stake,” said one MP, “and, though men may be generous with their own property, they should not be so with the property of others.” Abolition of the British trade could also give France an economic and naval advantage.

Before the parliamentary debates, Englishmen like John Locke, Daniel Defoe, John Wesley, and Samuel Johnson had already spoken against slavery and the trade. In a stuffy party at Oxford, Dr. Johnson once offered the toast, “Here’s to the next insurrection of the Negroes in the West Indies.’’

Amid such scattered protests, the Quakers were the first group to organize and take action against slavery. Those on both sides of the Atlantic faced expulsion from the Society if they still owned slaves in 1776. In 1783, the British Quakers established the antislavery committee that played a huge role in abolition.

The committee began by distributing pamphlets on the trade to both Parliament and the public. Research became an important aspect of the abolitionist strategy, and Thomas Clarkson’s investigations on slave ships and in the trade’s chief cities provided ammunition for abolition’s leading parliamentary advocate, William Wilberforce.

Leading parliamentary advocate, William Wilberforce.

Mockingly—and sometimes respectfully others called Wilberforce and his friends “the Saints,” for their Evangelical faith and championing of humanitarian causes. The Saints worked to humanize the penal code, advance popular education, improve conditions for laborers, and reform the “manners” or morals of England. Abolition, however, was the “first object” of Wilberforce’s life, and he pursued it both in season and out.

May 12, 1789, was clearly out of season for abolition. Sixty members of the West Indian lobby were present, and the trade’s supporters had already called abolition a “mad, wild, fanatical scheme of enthusiasts.” Wilberforce spoke for more than three hours. Although the House ended by adjourning the matter, the Times reported that both sides thought Wilberforce’s speech was one of the best that Parliament had ever heard.

Wilberforce had concluded with a solemn moral charge: “The nature and all the circumstances of this trade are now laid open to us. We can no longer plead ignorance.” Having failed to obtain a final vote, the abolitionists redoubled their efforts to lay open the facts of the trade before the British people. So far, the public had easily ignored what it could not see, and there had been no slaves in England since 1772. English people saw slave ships loading and unloading only goods, never people. Few knew anything of the horrors of the middle passage from Africa.

Over time, it became more and more difficult for anyone to plead ignorance of this matter. William Cowper’s poem “The Negro’s Complaint” circulated widely and was set to music. Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, by an African man named Ottabah Cugoano, also became popular reading. Thomas Clarkson and others toured the country and helped to establish local antislavery committees.

These committees, in turn, held frequent public meetings, campaigned for a boycott of West Indian sugar in favor of East, and circulated petitions. When, in 1792, Wilberforce again gave notice of motion, 499 petitions poured in. Although few MPs favored immediate abolition, this public outcry was hard to ignore.

An amendment inserting the word “gradual” into the abolition motion eventually carried the day. While in theory a victory of conscience, the bill as it then stood came to nothing. The abolitionist cause endured disappointments and delays each year following until 1804; and each year, British ships continued to carry tens of thousands of Africans into slavery in the Western Hemisphere.

Anxiety about the bloody aftermath of the French Revolution contributed to Parliament’s conservative, gradualist decision in 1792; and the next year brought war with France. Wartime England lost her fervor for the cause. Although Wilberforce stubbornly brought his motion in Parliament each year until 1801, only two very small measures on behalf of the oppressed Africans succeeded in the first decade of the war. Respect for Wilberforce and his ilk turned to annoyance, and many seconded James Boswell’s sentiments:

Go W— with narrow skull,

Go home and preach away at Hull…

Mischief to trade sits on your lip.

Insects will gnaw the noblest ship.

Go W—, begone, for shame,

Thou dwarf with big resounding name.

The state of affairs in France also brought abolitionist ideals under suspicion. One earl thundered:

“What does the abolition of the slave trade mean more or less in effect, than liberty and equality? What more or less than the rights of man? And what is liberty and equality; and what are the rights of man, but the foolish fundamental principles of this new philosophy?”

Even so, after more than a decade, the war with France began to lose its sense of urgency, however much the future of the world might—and did—hang in the balance. Slowly, public opinion began to reawaken and assert itself against the trade.

Conditions in Parliament also became more favorable. Economic hardship and competition with promising new colonies weakened the position of the old West Indians. In 1806 abolitionists in Parliament managed to secure the West Indian vote on a bill that destroyed three-quarters of the trade that was not with the West Indies. This bill, though in the West Indians’ competitive interest, also did much to pave the way for the 1807 decision.

On the night of the decisive 283-16 vote for the total abolition of the trade in 1807, the House of Commons stood and cheered for the persistent Wilberforce, who for his part hung his head and wept. The bill became law on March 25 and was effective as of January 1, 1808.

At home after the great vote, Wilberforce called gleefully to his friend Henry Thornton, “Well, Henry, what shall we abolish next?” Thornton replied, “The lottery, I think!”—but the more obvious answer was the institution of slavery itself.

For the next century, England fought diplomatic battles on many fronts to reduce the foreign slave trade. British smugglers were stopped in their tracks by the 1811 decision that made slaving punishable by deportation to Botany Bay. Smuggling under various flags threatened to continue the Atlantic trade after other nations had abolished it, and the British African Squadron patrolled the West African coast until after the American Civil War.

In 1833 slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire. This radical break was possible partly through an “apprenticeship” system, and a settlement to the planters amounting to 40 percent of the government’s yearly income. The news reached Wilberforce two days before his death. “Thank God that I should have lived to witness a day in which England is willing to give 20 million Sterling for the abolition of slavery,” he said.

Sometime before, Wilberforce had said, “that such a system should so long have been suffered to exist in any part of the British Empire will seem to our posterity almost incredible.” He was right. It is bittersweet, 200 years later, to commemorate the end of one of the most atrocious crimes in history. Yet the dismantling of an immensely profitable and iniquitous system, over a relatively short period of time and in spite of many obstacles, is certainly something to commemorate.

SLAVERY--SOME PHOTOS FROM 19 TH CENTURY OF SLAVERY IN AMERICA;SAME TYPE OF SLAVERY WAS GOING ON IN TRAVANCORE ALSO TILL 1850

BATTLE DURING SLAVE RIOTS IN HAITI 1802

Shows a woman carrying a weight chained to her ankle; in background, a man tilling ground with a hoe. The woman was judged guilty of not speaking when spoken to by a white person; for this she received 200 lashes and was forced to carry a 100 lb. weight chained to her ancle for several months

SLAVES

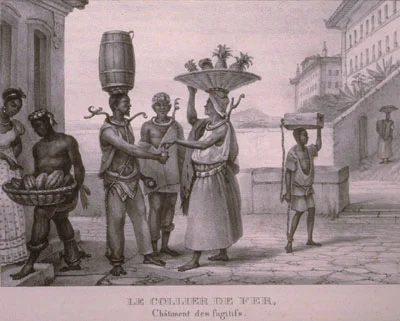

(Iron collar, punishment for runaways); urban scene, marketers of various goods; man/boy on right has weight on his head (also punishment for running away), attached to his ankle by a chain. The engravings in this book were taken from drawings made by Debret during his residence in Brazil from 1816 to 1831.

three men with their feet in stocks, surrounded by their cooking utensils. The engravings in this book were taken from drawings made by Debret during his residence in Brazil from 1816 to 1831.

executing the punishment of whipping/flogging); black man being whipped by public flogger in a town square; onlookers, others waiting to be flogged, soldiers guarding prisoners. The engravings in this book were taken from drawings made by Debret during his residence in Brazil from 1816

European whipping black on ground with arms and legs lashed together; background, black tied to tree being lashed by another black. The engravings in this book were taken from drawings made by Debret during his residence in Brazil from 1816

A Negro hung alive by the ribs to a gallows"; background shows skulls (presumably of beheaded slaves) on posts. This illustration was based on a 1773 eyewitness description. An incision was made in the victim's ribs and a hook placed in the hole. In this case, the victim stayed alive for 3 days until clubbed to death by the sentry guarding him who he had insulted.

man being broken on the rack (on the orders of the white authority) had been accused of stealing a sheep and shooting an overseer who discovered the theft. This method of torture was intended to keep the victim alive long enough to endure extreme pain before his eventual death. In this case, the victim's left hand was cut off before he died as additional punishment for theft and to serve as an example to others

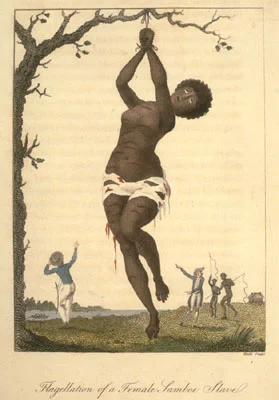

Caption, "Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave." Shows woman hanging from a tree with deep lacerations; in background two white men and two black men, the latter with whips. Stedman witnessed this punishment in 1774. The woman being whipped was an eighteen-year old girl who was given 200 lashes for having refused to have intercourse with an overseer. She was "lacerated in such a shocking manner by the whips of two negro-drivers, that she was from her neck to her ancles literally dyed with blood.

Pencil and sepia drawing by Charles Landseer, an English artist who visited Brazil when he was around 26 years old. The sketch shows a white (?) man whipping a black slave who is tied to a post and held by another black. Captioned "Black Punishment at Rio de Janeiro," there is no other information on this scene, which Landseer presumably witnessed during his stay in 1825-26.

(public punishment on St. Anne square); black whipping black with black and white onlookers.

Water color on paper titled "Punishing Negroes at Cathabouco [i.e., Calabouco], Rio de Janeiro"; shows unclothed black man tied to stake, being whipped by another black supervised by a white man. The English painter, Earle, visited Rio de Janeiro in 1820

FUGITIVE SLAVES ATTACKED BY DOGS

Slave hiding in a tree, trapped by armed whites on horseback; dogs surrounding tree. Illustration

Caption, "running away"; fugitives trying to elude white captors. The Fugitive Slave Act (1850) authorized slave catchers to track down runaway slave

man on left being flogged, in center at bottom, a woman has her hair cut off.

Trial and imprisonment of Jonathan Walker, at Pensacola, Florida, for aiding slaves to escape from bondage

A woman with Iron Horns and Bells on, to keep her from running away"

"This is a machine used for packing and pressing cotton. By it, he hung me up by the hands at letter a, a horse moving round the screw

Title, "Food for Criminals," shows prisoners in the Rio jail taking "the daily pittance" of food for "their miserable brethren in Gaol." The man on the left carries a box containing bread or biscuit, while the iron pot suspended from the pole contains "the soup, meat, and vegetables." The "worst and most hardened" of the prisoners are "distinguished by irons round the leg, in addition to those on the neck"

THE DALITS OF KERALA WAS KNOWN AS UNTOUCHABLE CASTES ;BY THE HIGHER CASTES .

MANY LOWER MOST IN THE CASTES WERE ALSO SLAVES

AND THEY COULD BE SOLD ALONG WITH PROPERTY

AND CRUEL PUNISHMENTS WERE GIVEN FOR ANY REASON -TILL SLAVERY WAS ABOLISHED IN TRAVAN CORE IN 1855

"The missionaries’ anti-slavery campaign and their continued pressure on the Travancore government finally ended in the emancipation of the slaves. On 24 June 1855 it was declared that owning slaves was illegal."

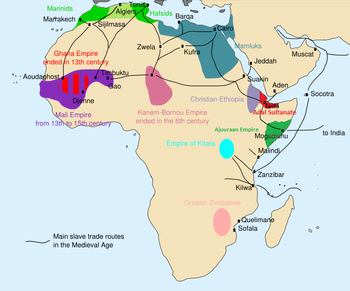

Over 28 Million Africans have been enslaved over the Muslim world over the past 14 centuries

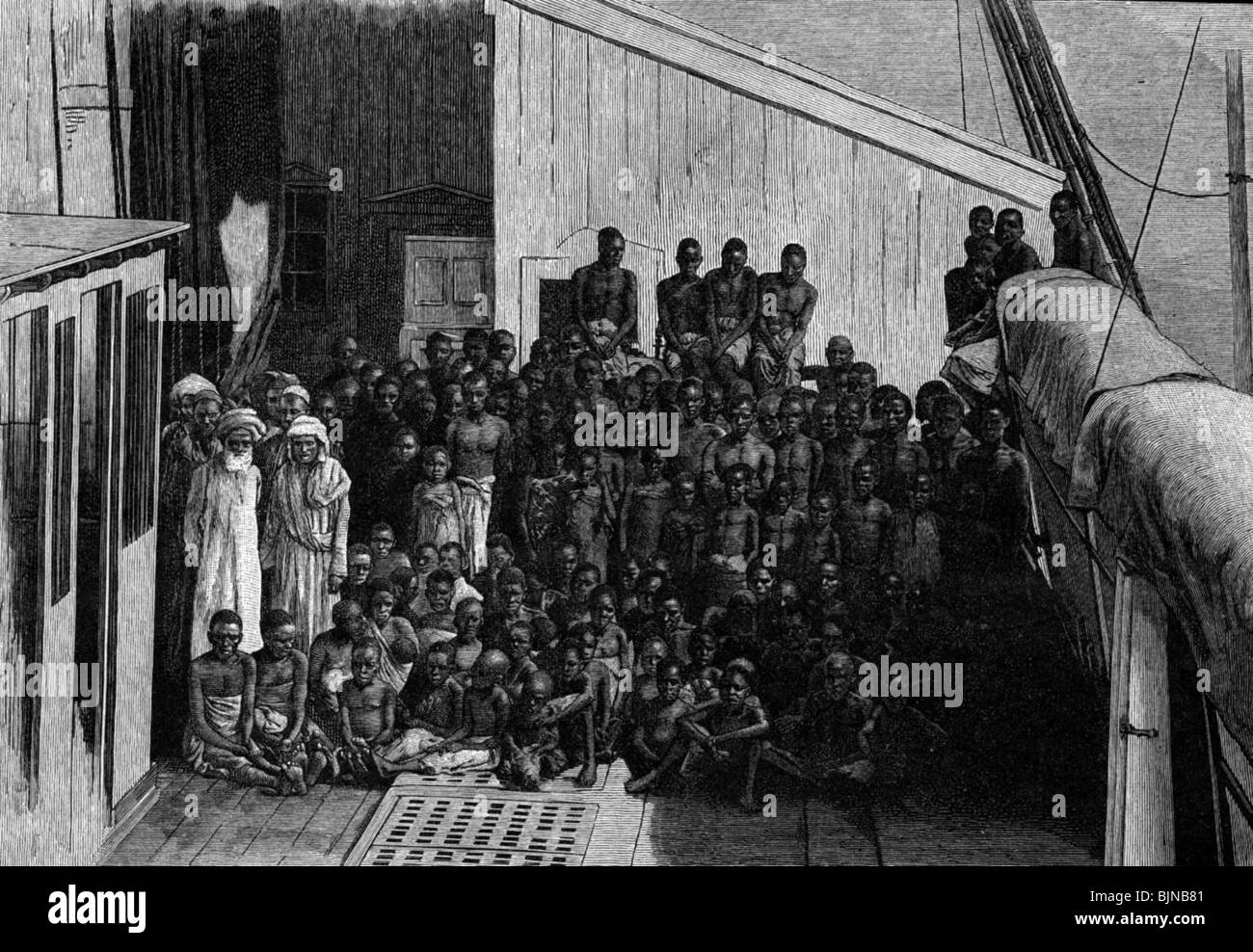

Slaves in Africa - in the early 20th century

British slave traders made maximum profit

About 80% those captured by Muslim slave raiders died before Reaching the slave markets

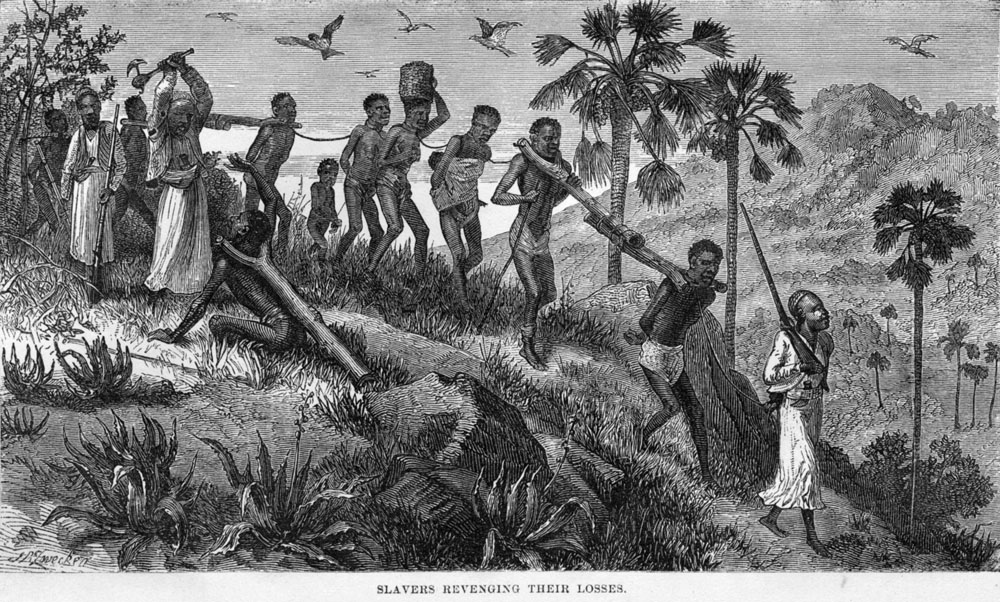

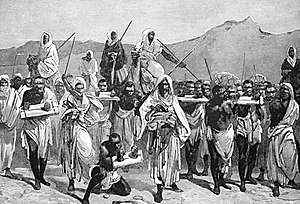

An Arab slave raid in East Africa 1888. The death toll from 14 centuries of the Islamic slave trade in Africa is estimated at over 112 million.

Arab traders beat their cargo into submission on the run from the African coast to Zanzibar

The slave market in Zanzibar sold an average of 300 slaves every day

Arab slave traders along the Ruvuma River, East Africa, 1866, axe a straggler.

Muslim slave raiders kidnapped women from Europe for harems in the Middle East.

A steam pinnache of HMS London puts a warning shot across the bow of a slaving dhow in 1881.

Rescued from slavery by the British Navy, Samual Crowther became the first African bishop of the Church of England.

Newly liberated slaves in Zanzibar.

Livingstone and his team free slaves from Arab slave raiders in the Shire Valley.

1833 - All slaves in the British Empire are set free by Parliamentary decree.

An Arab slave caravan, crossing the Sahara Desert. Ibn Battuta traveled with such a party when he came home from Mali in 1353; his group had 600 female

SLAVES

The Europeans and Arabs couldn't have taken away as many slaves as they did without African cooperation. Usually Africans caught the slaves first; here we see a slave coffle being delivered to the coast, where the Europeans waited to buy them.

How can I view the records covered in this guide?

How many are online?

- None

- Some

- All

Contents

- 1. Why use this guide?

- 2. A brief introduction to the slave trade and its abolition

- 3. An overview of the records at The National Archives

- 4. Records relating to transportation of slaves and goods

- 5. Campaign for abolition of the slave trade

- 6. Post-abolition of the slave trade

- 7. Records of ex-slaves and liberated Africans

- 8. The enslaved and resistance

- 9. Records of plantations

- 10. Abolition of slavery

- 11. Records in other institutions

- 12. Further reading

1. Why use this guide?

Use this guide for an overview of records held at The National Archives that shed light on the slave trade, slavery and unfree labour in the British Caribbean and North American colonies. The guide is by no means exhaustive, but introduces and illustrates the diverse range of documents related to the transatlantic slave trade held here.

The guide covers records created throughout the trade, from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The wide range of documents, inherited from various government departments, illustrates the extent and impact of the trade at the time.

This is not a history of the transatlantic slave trade. For background history, please see suggested further reading and the Education section of The National Archives’ website.

2. A brief introduction to the slave trade and its abolition

The transatlantic slave trade was essentially a triangular route from Europe to Africa, to the Americas and back to Europe. On the first leg, merchants exported goods to Africa in return for enslaved Africans, gold, ivory and spices. The ships then travelled across the Atlantic to the American colonies where the Africans were sold for sugar, tobacco, cotton and other produce. The Africans were sold as slaves to work on plantations and as domestics. The goods were then transported to Europe. There was also two-way trade between Europe and Africa, Europe and the Americas and between Africa and the Americas.

Britain was one of the most successful slave-trading countries. Together with Portugal, the two countries accounted for about 70% of all Africans transported to the Americas. Britain was the most dominant between 1640 and 1807 and it is estimated that Britain transported 3.1 million Africans (of whom 2.7 million arrived) to the British colonies in the Caribbean, North and South America and to other countries.

Anti-slavery campaigners lobbied for twenty years to end the trade and the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed in Britain on 25 March 1807. It was declared that from the 1 May 1807 ‘all manner of dealing and reading in the purchase, sale, barter, or transfer of slaves or of persons intending to be sold, transferred, used, or dealt with as slaves, practiced or carried in, at, or from any part of the coast or countries of Africa shall be abolished, prohibited and declared to be unlawful’. Slavery was abolished in 1834 but in reality for many of those enslaved it continued until at least 1838 through apprenticehip schemes.

3. An overview of the records at The National Archives

Records held at The National Archives reflect Britain’s involvement in the trade and its abolition through a wide range of records and record series, such was its importance to the country at the time. These include records of the Colonial Office (CO), Board of Trade (BT), Chancery (C), Admiralty records (ADM) and Treasury records (T), among other government departments.

The most important records for the study of Caribbean slavery in The National Archives are in the records of the Colonial Office. There are separate series for each country. The important series include:

- original correspondence: official letters and reports from the governor of the territory to the Colonial Office, and may include newspapers, petitions from slave owners and freemen, reports on slave rebellions, correspondence on local and British laws affecting slaves, statistics on slave populations, reports on slave imports and exports, and court cases against slaves or owners

- sessional papers: reports of the local government on all matters affecting the country and may include grants of freedom and discussions on slave laws

- acts: these contain manuscript and printed local laws

- newspapers and early official gazettes: may contain reports of runaways, notices of slave auctions and sales of property (which may include slaves). The National Archives holds a few collections of colonial newspapers, mostly for the 1830s-1850s. These are in Colonial Office ‘miscellanea’ series, although occasional newspapers can be found as enclosures to governor’s despatches in original correspondence

The Colonial Office records are not well catalogued and will need some time and effort to work through. For further information on how to search these record series, see our research guide on records of Colonies and dependencies from 1782.

However there are relevant records in a wide range of other series. For example, the early stages of the transatlantic trade can be traced in the charters granted by the government to merchants for trade with Africa in goods and then later slaves in the Patent Rolls in C 66.

These charters include the creation of the Company of Royal Adventurers of England Trading with Africa, the largest single British company involved in the transatlantic trade, whose settlements and papers were passed to the Treasury. They are now held at The National Archives in the T 70 series and can be searched by date and often location in Discovery, our catalogue.

Copies of the Acts passed by the British Parliament relating to slavery and the slave trade are available in the library at The National Archives and are usually in major reference libraries. Most relevant laws passed are available through www.pdavis.nl/Legislation.htm and online at Hansard. Most of the legislation relates to the slave trade rather than to slavery itself, as the latter was managed and legislated under local colonial laws.

| Suggested documents of interest | Catalogue reference |

|---|---|

| Account of English sugar plantations | CO 1/22 no 20 |

| Examples of Barbadian slave laws | CO 30/2 |

| Description of licence granted to the South Sea Company | T 52/26 pp.196-206 |

| Order in Council (1805) regarding slave licences | PC 2/168 pp.227-231 |

4. Records relating to transportation of slaves and goods

Ships involved in the colonial trade were first required to be registered in 1696. Registers survive from 1786 in BT 6/191-193 and BT 107 (indexes in BT 111). Only four volumes for Liverpool, 1739-1774, have survived for ships registered before 1786 because of a fire at Customs House. These registers are held by the Merseyside Maritime Museum.

Prior to clearing from a British port, the master first had to obtain a pass from the Admiralty. These licenses and those relating to travelling in convoy are in ADM 7. At the port, the master of the ship had to provide the collector of customs with a written list of the cargo to calculate duty. The details were written up in Port Books (E 190). Other records may have been collected at the various customs houses (the records of customs out ports are in CUST series), however many have been lost due to fires, riots and war. In addition to customs duty, between 1698 and 1713 British merchants involved in the Africa trade had to pay 10% tax on goods exported to Africa. This tax was levied to maintain the African Company’s forts etc. The duty ledgers are in T 70/349-356.

Ships’ captains maintained log books or journals which described details of voyages. These log books were the property of the ship owners and may survive in local record offices. Very few have been found in The National Archives; those that have are the log books of Royal African Company ships in T 70.

The master also lodged a muster with the collector of customs on the ship’s return, some of these can now be found in BT 98 (for example the muster of the Otter in BT 98/68 no 127). However, only those for Liverpool survive before 1807. Some musters and crew lists may survive in the archives of port towns and cities.

Information relating to goods imported to and exported from Africa can be found in the duty ledgers, accounts and correspondence of the African companies in T 70, especially among records of their forts, factories and settlements on the West Coast of Africa. Other papers can be found in the correspondence and registers of the Board of Customs (CUST 3 and CUST 17), the Board of Trade (CO 388 to CO 391), the Treasury (T 1), and in the Port Books (E 190).

5. Campaign for abolition of the slave trade

Researchers looking at the campaign for abolition will find material in a wide variety of regional collections and personal papers. As the campaigns were organised in different towns and cities across the country, it is well worth searching for sources in local collections.

The formal abolition campaign was launched in 1787. The campaign in Parliament can be followed in printed parliamentary debates and in Parliamentary Papers. A full list can be found online at Hansard. It is often worth checking parliamentary papers for any large event involving the slave trade as it is likely it was mentioned, if not discussed, in Parliament.

Enslaved Africans played a role in abolition with regular and persistent resistance. Search our catalogue, limiting the record series to ‘CO’, and using key words such as ‘slave AND rebellion’ and ‘slave AND uprising’. The abolitionist campaign after 1791 was greatly affected by the slave revolt in Saint Domingue and, after 1793, by the war with revolutionary France. Records relating to both events can be found in The National Archives in series such as T 81, T 64, CO 137, CO 245, ADM 1, WO 1, FO 27 and FO 72.

The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed in Britain in March 1807. But the international campaign against slavery (as distinct from the trade) continued and it was not until 1833 that legislation was passed in the British Parliament starting the process for the abolition of slavery itself. See the following section for further information.

6. Post-abolition of the slave trade

6.1 Records of the anti-slavery movement

After 1807 the British anti-slavery movement entered a new phase. The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade gave way to the African Institution. Papers on the African Institution can be found at the British Library (the Institution’s published Reports). Further research into the congresses can be pursued in FO 27; FO 84/1-2; FO 92/1, 4, 7-8, 17-22; FO 95/9/2; and FO 139/46. Other sources include personal papers that can be found at the British Library and in local archives and repositories. Find these by searching our catalogue and filtering your results to only show those from other archives.

6.2 Diplomatic efforts to suppress the slave trade

FO 84 is the main Foreign Office series relating to diplomatic efforts on the suppression of the slave trade 1816-1892. However, other material relating to Africa is to be found in FO 2 – this overlaps with FO 84 and covers the period 1825-1874 and 1893-1906. Also, each country has a separate general correspondence series in FO series, which have annual headings for the slave trade. See the research guide on Foreign Office and Foreign and Commonwealth Office records from 1782 for further information. Search Discovery, our catalogue, within FO (and particularly FO 84 and FO 2) using keywords such as ‘slave’ and ‘slave AND [name of country]’.

Foreign Office treaties with other sovereign countries and colonial powers are in FO 93 with ratifications in FO 94. These series include treaties with African powers where the Foreign Office handled negotiations. You can find these treaties by searching our catalogue using such keywords as ‘Spain AND slave’ restricting the search in the series or department field to ‘FO 93, FO 94’. Treaties made by naval officers, colonial officials, or governors of chartered companies on behalf of the Crown are in the relevant correspondence series – usually by date of treaty. These are not indexed and you will usually need to know the date of the treaty and the parties involved. Many important treaties have been published in the annual series State Papers, British and Foreign. Treaties relating to Africa, including many made by naval officers and colonial officials are published in Hertslet’s Map of Africa by Treaty. Copies of some treaties have been published as Colonial Office confidential print in CO 879: search our catalogue using keyword ‘Africa’ or names of individual territories.

6.3 Naval records relating the suppression of the slave trade

The Royal Navy played a key role in Britain’s efforts to suppress the slave trade, including seizing ships believed to be involved in the illegal trade. These ships could then be tried at Mixed Commission Courts and vice-Admiralty courts.

ADM 1 contains letters and reports from captains of the several naval stations. In addition it contains correspondence from the Colonial Office, Foreign Office and the Treasury relating to anti-slaving patrols and slaving intelligence and occasionally proceedings of Mixed Commission Courts and vice-Admiralty Courts. The Commander-in-Chief papers are listed separately in our catalogue but you will need to use the registers in ADM 12 for other papers. See the research guide on Admiralty Index and Digest: ADM 12 for more details, and try keyword searches within ADM, with terms such as ‘slave’ and ‘slave AND ship’

Ships’ logs in ADM 51 and ADM 53 give accounts of sightings, chases and the capture of slavers. The musters of anti-slaving ships in ADM 37 sometimes list freed Africans in the section headed ‘supernumeries’. These records are arranged by the name of the Royal Naval ship and then by date. See the research guide on Royal Navy: operational records 1660-1914 for further information.

Slavers found to be acting illegally were condemned and ships and their possessions could be sold. There do not appear to be many bounty or prize lists awarding payment for anti-slaving activities but occasional lists can be found in T 1, ADM 48 and ADM 1.

6.4 Records of court cases, and further records

For records of the Mixed Commission Courts across The National Archives’ collection, search our catalogue using keywords ‘mixed commission AND slave’. Records of these courts can also be found in the records of the various slave trade commissions.

The most important series relating to cases of illegal slavers outside those of the Mixed Commission Courts are the records of the Slave Trade Adviser to the Treasury. Papers from 1821 are in:

- HCA 35 – Report Book, 1821-1891

- HCA 36 – Unregistered Papers, 1837-1876

- HCA 37 – Registered Papers, 1821-1897

Most records and proceedings of vice-Admiralty courts in the colonies are to be found, where they survive, in the archives of the relevant country. However, some proceedings and other papers, especially those relating to the suppression of the slave trade can be found among the records of the High Court of Admiralty (HCA), Board of Customs (CUST) and the records of the Colonial Office (CO) from the governors, clerks of vice-Admiralty Courts and collectors of customs.

Other papers relating to the suppression of the slave trade are to be found in Treasury and Colonial Office records especially T 1 and CO 267 (for Sierra Leone), and CUST 34 (Board of Customs papers relating to the colonies). Often these are duplicates of what is found in HCA, ADM and FO series, but sometimes these contain papers that have been destroyed from the more likely series.

| Examples of documents of interest | Catalogue reference |

|---|---|

| Records of the slave ship Eliza | BT 98/69, no 264; ADM 7/122f.101; ADM 7/804; CO 33/23 |

| Papers from the vice-Admirality Court at Sierra Leone (1808-1817) | HCA 49/97 |

| Records of the slave ship Henriqueta (later renamed the Black Joke and used to capture illegal slavers) | ADM 51/3466; FO 84/66 f.203-209; FO 315/65/60; FO 315/31; ADM 1/1; ADM 1/74 |

7. Records of ex-slaves and liberated Africans

7.1 Court and customs records

There are some records relating to ‘liberated Africans’ who were found onboard illegal slavers and freed by vice-Admiralty and Mixed Commission Courts. These ex-slaves were not technically free: able-bodied men were ‘enlisted’ into the military services particularly the army, in regiments such as the Royal Africa Corps and the West India Regiment for unlimited service. Women and children were often apprenticed to local landowners, to the military and to the local government.

There is very little information on individual liberated Africans – very few vice-Admiralty Court proceedings are to be found in The National Archives (see above). Admiralty papers especially ADM 1, and CUST 34, HCA 30 and HCA 49 contain a few lists of the slaves liberated. Two Sierra Leone censuses have information relating to liberated Africans: CO 267/111 (1831) and CO 267/127 (1832-1834). Because the collectors of customs were responsible for looking after liberated Africans, information can sometimes be found in Colonial Office original correspondence series, especially in despatches from the governor, the naval office and the Board of Customs and in CUST 34. A ‘Commission of Enquiry into the state of captured Negroes in the West Indies, 1821-1830’ (CO 318/81-98) was set up to look at the treatment and conditions of liberated Africans in the West Indies and includes some lists of liberated Africans.

In 1817 collectors of customs were required to send annual reports on liberated Africans they received to the Colonial Secretary. No annual returns have been found among Privy Council or Colonial Office records although some returns which pre-date this were printed for Parliament in 1821; others may be found among the Commission of Enquiry schedules in CO 318/81-98.

7.2 Movement of ex-slaves

Schemes were proposed to move liberated Africans from the more densely populated colonies to those which needed labourers such as Trinidad and British Guiana and correspondence relating to these schemes is found in relevant CO original correspondence series, such as CO 295 for Trinidad. An agreement was also made between Britain and Spain to send some free blacks from the Spanish colony of Cuba to British possessions, especially Trinidad. Correspondence relating to this movement for the period 1835-1842 is in CO 318. Key word search these record series using terms such as ‘slave’ and ‘liberated African’, and country names.

| Examples of documents of interest | Catalogue reference |

|---|---|

| Records of female slaves ‘freed’ and apprenticed as domestics | CO 28/85 f 52 |

| Records relating to the establishment of a settlement at Kingstown, Antigua (1831), following overcrowding on Tortola due to the numbers of slaves released by the vice-Admiralty Court | CO 239/25; CO 700/virginislands6; T 1/4303; CO 239; CO 239/13; HCA 49/101; CUST 34/816; HCA 30/816; HCA 30/796; CO 318/82 |

8. The enslaved and resistance

It is important to note that the majority of records of the slave trade are written from the viewpoint of those generally controlling the trade, and very little information is available about enslaved Africans themselves. Durint transportation across the Middle Passage (the journey between Africa and the Americas), slaves were classed as ‘goods’ and would usually only be noted in ships’ logs on death, if at all. There are few records relating to the Middle Passage because the voyages were private ventures. Some information on African Company slave losses should be found in T 70 which can be searched by date and often location. Following transportation, slaves on plantations were barely noted. Until the introduction of slave registers it is usually only through court cases and correspondence that they are occasionally found.

8.1 Registers and returns of slaves

There are some registers of slaves created to monitor slave holdings and the importation of slaves into British colonies between 1814 and 1822, duplicates of which are in the series T 71. The first registration for each colony is a complete list of all slaves. Subsequent returns usually only record increases or decreases to the slave populations such as births, deaths, bequests, purchases etc. Many of the returns record where the slave was born so it is possible to identify slaves born in another country and several returns indicate if a slave was exported or imported since the last return.

Although Britain transported around 3.1 million enslaved Africans, only around 2.7 million arrived at their destination largely due to deaths while travelling the Middle Passage (the journey between Africa and the Americas). There are few records relating to the Middle Passage because the voyages were private ventures. Slaves were classed as ‘goods’ and their deaths were supposed to be accounted for and noted in the ship’s log. Some information on African Company slave losses should be found in T 70 which can be searched by date and often location.

8.2 Records of government-owned slaves

The British Army and Royal Navy owned and hired slaves as labourers and soldiers, most of whom went to the Corps of Military Labourers and the West India Regiments. CO 318/31 describes army purchases of slaves for the West Indian Regiments including the numbers purchased. There are several files in WO 1 relating to the status of slaves in the Army, especially once they were discharged.

Estates were occasionally passed to the Crown in lieu of government taxes and following court cases. An example is Greenwich Hospital (ADM 65/59), which was managed by a government department for a number of years and took over Golden Vale plantation in Portland Parish, Jamaica in 1793.

For further information on government-owned slaves, researchers should check musters for dockyards, ships, and regiments. It is also possible that some former slaves may have discharge papers or applied for pensions so there may be papers in WO 97and ADM 29. WO 97 for the period 1760-1854 is searchable online by country of birth and by regiment through findmypast.

8.3 Resistance

It was primarily Africans newly-arrived in the Americas who rebelled against their enslavement. However it was not unknown for Creole slaves to rebel, as was experienced with Bussa’s Rebellion in Barbados in 1816 (CO 28/85) and the last great rebellion in Jamaica over Christmas 1831 and the New Year 1832 (CO 137/184).

Running away was the most common form of resistance, and Caribbean newspapers are full of notices for runaways (for example CO 7/1 – Barbados 1786 & 1789; CO 71/2 – Dominica, 1798; CO 137/14 – Jamaica, 1771-1772; CO 260/48 St Vincent, 1831).

See section 7 above for records of ex-slaves and liberated Africans.

| Examples of documents of interest | Catalogue reference |

|---|---|

| Case of the Zong massacre (1781) | KB 122/479; KB 125/168; KB 168/150 f.53; E112/1528 no 173; E 127/47 |

| First references to Africans (called ‘Negroes’) in Colonial America | CO 1/3 nos 2 and 35 |

| Log of the James describing slave mortality in the Middle Passage | T 70/1211, f.100 |

| ‘Book of Negroes’ – a list of men, women and children bound for Nova Scotia on British ships after the American War of Independence. | PRO 30/55/100 (searchable copy available from Nova Scotia archives) |

9. Records of plantations

Plantation records are the private papers of the plantation owner and their family. As with private papers in general, very few survive. Papers are to be found in local and specialist repositories in the Caribbean, the UK and elsewhere. Search our catalogue and refine your results using the filters. For further information on the whereabouts of plantation papers, see Peter Walne, Guide to Manuscript Sources for the History of Latin America and the Caribbean in the British Isles (1973).

There are few plantation accounts in The National Archives, mostly found as exhibits to equity cases resulting from disputes about land, debts or marriage settlements. These can be found in record series C 103–C 115: run a key word search limited to these series, using key words such as ‘plantation’. Private papers are also found in the records of two commissions: the West Indian Encumbered Estates Commission, 1854-1893 in CO 441, and the West Indian Hurricane Relief Commission, 1832-1881 in PWLB 11. Although these commissions were essentially set up after the abolition of slavery, many of the records predate emancipation and have some information on slave holdings.

| Examples of documents of interest | Catalogue reference |

|---|---|

| Plantations in Antigua | CO 700/Antigua2 |

| Map of Barbados with illustration of plantation | CO 700/Barbados9a |

| Martin v Bothall – account of stock including slaves | J 90/399 |

| Blenheim and Cranbrooke plantation accounts | WO 9/48 |

10. Abolition of slavery

Although the slave trade was abolished in 1807, slavery was not abolished until 1834. Those already enslaved remained so, and some records exist in relation to the ongoing situation and the amelioration of slaves.

In 1823, following debates in the British Parliament to improve slave living and working conditions, the Colonial Secretary issued instructions for the governors to send returns of the numbers of slave imported or exported between colonies. These instructions were reissued on a number of occasions until 1830. Most governors sent statistical returns and a few sent nominal returns. These returns are in Colonial Office Original Correspondence series and a few were printed for Parliament and are to be found in Parliamentary Papers.

For other records relating to schemes for the ‘amelioration’ of slaves and ex-slaves, search our catalogue using the terms ‘slave AND amelioration’.

When slavery was abolished, legislation followed which awarded colonial planters twenty million pounds in compensation. Many of the records generated by the Slave Compensation Commission, set up to distribute the funds survive, among them original claims and certificates, counter-claims, commissioners’ hearing notes, and lists of awards. The records of the Office of Registry of Colonial Slaves and Slave Compensation Commission, 1812-1851, are in T 71. AO 14/37-48 documents the awards of compensation made by the Claims Commissions, 1834-1845. NDO 4 includes registers of compensation paid to slave owners 1835-1842

11. Records in other institutions

For further records relating to the transatlantic trade, it is well worth investigating local record offices, particularly in large slave trading ports such as Liverpool, Bristol and London. Some key places to search are suggested here:

- The British Library – records of the East India Company

- Mundus (Internet archive)- missionary records in Africa

- Hakluyt Society – records of 16th and 17th century trading voyages with Africans

- Parliamentary Archives – abolitionist petitions

- Legacies of British slave-ownership database – records of slave-owners

Personal abolitionist papers, publications and plantation papers in the UK can be found by searching our catalogue and refining your results using the filters.

12. Further reading

Some of the publications below may be available to buy from The National Archives’ bookshop. Alternatively, search The National Archives’ library catalogue to see what is available to consult at Kew.

The slave trade and slavery: records at The National Archives

- Guy Grannum, Tracing Your Carribean Ancestors (third edition, Bloomsbury, 2012)

- Access Calendar of State Papers, Colonial: North America and the West Indies from colonial.chadwyck.com

- Acts of the Privy Council, Colonial series (HMSO, 1908-1912)

The enslaved and resistance

- Michael Craton, Testing the chains: Resistance to slavery in the British West Indies (Cornell University Press, 1982)

Transportation of slaves and goods

- Joseph C Miller, Mortality in the Atlantic slave trade: Statistical evidence on causality, Journal of interdisciplinary history, vol 11, 1981, pp385-423

- Bruce L Mouser’s A slaving voyage to Africa and Jamaica: The log of the Sandown, 1793-1794 (Indiana University Press, 2002)

Plantation Records

- HMSO, Journal of the Commissioners for Trade and Plantations (HMSO, 1920-1938)

- Peter Walne, Guide to manuscript sources for the history of Latin America and the Caribbean in the British Isles (Oxford University Press for the Institute of Latin American Studies, University of London, 1973)

Campaign for abolition

- Roger Anstey, The Atlantic slave trade and British abolition 1760-1810 (Macmillan, 1975)

- Reginald Coupland, The British anti-slavery movement (F Cass, 1964)

- Elizabeth Heyrick, Immediate, not gradual abolition (1824)

- Clare Midgley, Women against slavery: The British campaigns, 1780-1870 (Routledge, 1992)

- JR Oldfield, Popular politics and British anti-slavery: The mobilisation of public opinion against the slave trade, 1787-1807 (Routledge, 1998)

Post-abolition

- Norman Buckley, Slaves in red coats: British West India regiments, 1795-1815 (Yale University Press, 1979)

- Thomas B Howell, A complete collection of state trails and proceedings for high treason and other crimes and misdemeanors (TC Hansard for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1816-1826)

- WEF Ward, The Royal Navy and the slavers (Allen & Unwin, 1969)

Records of ex-slaves and ‘liberated Africans’

- Stephen J Braidwood, Black poor and white philanthropists: London’s blacks and the foundation of the Sierra Leone settlement 1786-1791 (Liverpool University Press, 1994)

- James W St G Walker, The Black Loyalists: The search for a promised land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783-1870 (Africana Publishing Company, 1976), pp413-414

General history

- Roger Anstey, Liverpool, the African slave trade and abolition: Essays to illustrate current knowledge and research (Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1976)

- Black History Resource Working Group, Slavery: An introduction to the African holocaust with special reference to Liverpool – ‘capital of the slave trade’ (second edition, 1997)

- Brycchan Carey, Discourses of slavery and abolition: Britain and its Colonies (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004)

- Madge Dresser, Slavery obscured: The social history of the slave trade in an English provincial port (Continuum, 2001)

- Paul Geoffrey Edwards and James Walvin, Black personalities in the era of the slave trade (Louisiana State University Press, 1983)

- David Eltis and David Richardson (eds), Routes to slavery: direction, ethnicity and mortality in the transatlantic slave trade (Routledge, 1997)

- Olaudah Equiano, The interesting narrative and other writings, ed Vincent Carretta (Penguin Books, 2003)

- Peter Fryer, Staying power: The history of black people in Britain (University of Alberta, 1984)

- Paul E Lovejoy, Transformations in slavery: A history of slavery in Africa (second edition, Cambridge University Press, 2000)

- Lowell J Ragatz, A checklist of House of Commons sessional papers relating to the British West Indies and to the West Indian slave trade and slavery 1763-1834 (Bryan Edwards Press, 1923)

- Edward Reynolds, Stand the storm: A history of the Atlantic slave trade (IR Dee, 1993)

- David Richardson, The Bristol slave traders: A collective portrait (Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 1985)

- Nigel Tattersfield, The forgotten trade: comprising the log of the Daniel and Henry of 1700 and accounts of the slave trade from the minor ports of England, 1698-1725 (Jonathan Cape, 1991)

- Hugh Thomas, The slave trade: The history of the Atlantic slave trade, 1440-1870 (Simon & Schuster, 1999)

- James Walvin, An African’s life: The life and times of Olaudah Equiano, 1745-1797 (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000)

- James Walvin, Black ivory: Slavery in the British empire (second edition, Wiley-Blackwell, 2001)

- James Walvin, Making the Black Atlantic: Britain and the African diaspora (Cassell, 2000)

- A checklist of House of Lords sessional papers relating to the British West Indies and to the West Indian slave trade and slavery, 1763-1834 (Bryan Edwards Press, 1932)

No comments:

Post a Comment