Taste of life: Bulk-buying set-up rescues kitchen at Poona’s “Fever Hall”

Under the new regime, Gousse (a Scottish doctor) bought all the necessary articles in bulk, kept them locked up, and served out what was wanted each morning. This method was troublesome too, but much less so than the daily wrangling over each account, and their household expenses fell by nearly 50 per cent

When Dr Phillipe Gousse, a Scottish doctor, was asked to move to King George’s War Hospital in Poona from Bangalore, in August 1917, the First World War was nearing its end. The Great War had not reached the shores of India and he expected to go back to Europe in a couple of years. He was a “camp-follower” – a slightly derogatory term used for doctors of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), whose job it was to tend to wounded soldiers, and look after the sanitation of camps.

Gousse and five other doctors from the RAMC rented a bungalow, known locally as the “Fever Hall”, next to the Empress Gardens, from a Parsi race-horse owner. The hospital still had no patients in it.

The inhabitants of Fever Hall had employed a butler who was paid a fixed sum per head. It was left to him to feed them, engage and pay a cook, and supply everything down to wood for the kitchen fire and oil for the lamps. This arrangement, which sounded simple, was supposed to save the doctors from all the worries of housekeeping. What actually happened was that the butler underpaid the cook, bought the very cheapest meat, and smothered it in strong curry powder. “It is curry for breakfast, curry for lunch and curry for dinner, and bellyache all night”, wrote Gousse in his diary.

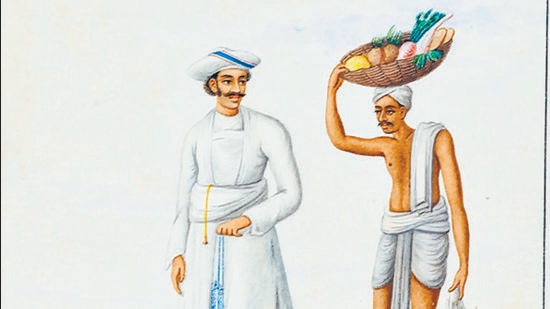

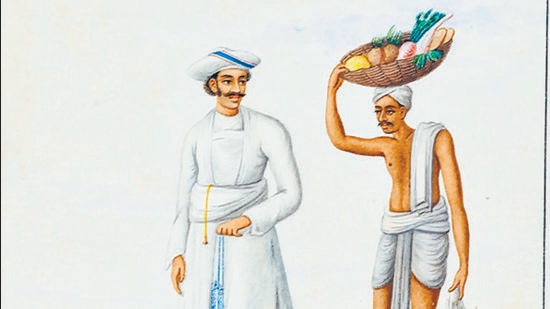

So Gousse sacked both the butler and the cook, and engaged a new butler, Wharri Ahmed, a dignified gentleman with a flowing black beard, and a “Goanese” cook. The cook wore a “topee” on his head so that he could claim to be of European descent. His name was Manuel Joao Domingo Francisco de Xavier Jesus de Gama.

Every morning Wharri and Gousse discussed the day’s bill of fare. It was a tiresome and irritating proceeding, “for there was not only the language difficulty, but the utterly incomprehensible oriental mind of Wharri, and to Wharri, no doubt, my own equally inscrutable occidental one”, wrote Gousse. Anyhow, the new system worked well for a time and the doctors got somewhat tasty European food, properly cooked by Manuel de Gama.

There were, however, drawbacks to this method. It was annoying to have to order daily small amounts of everything and check the cost of each item in Wharri’s account, and there was also the expense. Gousse wrote in his diary – “Wharri’s daily household accounts cover the whole one side of a sheet of foolscap paper, and contains thirty-two separate items with the price of each. When it is remembered that the Indian rupee was worth one shilling and six pence, an anna one penny and a pie about a third of a farthing, the reader of these lines, will appreciate the trouble I had brought upon myself”.

“Here are a few entries as a sample of the rest, in the order in which Wharri wrote them down: Soopa – 3 annas, Underpart Beef – 8 annas, Kiddney – 2 annas, New green stuff – 9 pies, Frut – 4 annas, passly and salry – 6 pies, oranges – 5 annas, curry stuff – 2 annas, cocknut – 2 annas, munkeynut – 1 anna, char col – 1 anna, 6 pies, firewood – 12 annas, oil 2 bottles – 4 annas, 6 pies, coolis – 6 annas”.

Wharri also received an infinitesimal commission from the vendor at the bazaar, where he spent his mornings shopping and bargaining. Wearied of this retail way of housekeeping, Gousse decided to step in. Instead of buying a day’s supply of firewood at a time for the cook’s fire for twelve annas and paying two “coolies” six annas to bring it to the bungalow from the bazaar, he purchased a whole bullock-cart load of firewood for twelve rupees and paid twelve annas for having it brought up. “In the old way this firewood would have cost us fifteen rupees and about six rupees for the coolies who brought a little quantity each day”, Gousse wrote.

From then on, everything was purchased in the same way, even things which they used in small quantities daily, such as charcoal, salt, and curry powder. Under the new regime, Gousse bought all the necessary articles in bulk, kept them locked up, and served out what was wanted each morning. This method was troublesome too, but much less so than the daily wrangling over each account, and their household expenses fell by nearly 50 per cent.

The Australian nurses employed in the Camp and the hospital soon learned about Gousse’s modus operandi and decided to buy groceries in bulk.

Europeans living in British India often found themselves in similar situations. The Raj had introduced a completely new style of kitchen to India, with upright stoves and shelves, benches, sinks. The cook had to learn to work at the bench to chop vegetables and meats. The butler had to learn English in order to understand what the memsahib wanted for lunch. They both had to struggle with the European dishes and their ingredients.

In the eyes of both the European memsahib and her Indian butler, “Europe articles” held great prestige. These were available at the local “Europe shop”, of which there was one in almost every army station. To help the memsahib (and her butler), Raj-era cookbooks and domestic manuals often contained a “Bazaar list”. This list was meant to help with the purchases. It contained names of common ingredients and their prices. There were separate lists for bazaars in Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, Bangalore, and Deolali.

I have found only a couple of cookbooks that had the “Bazaar list” to be used in Poona. More about them next week.

No comments:

Post a Comment